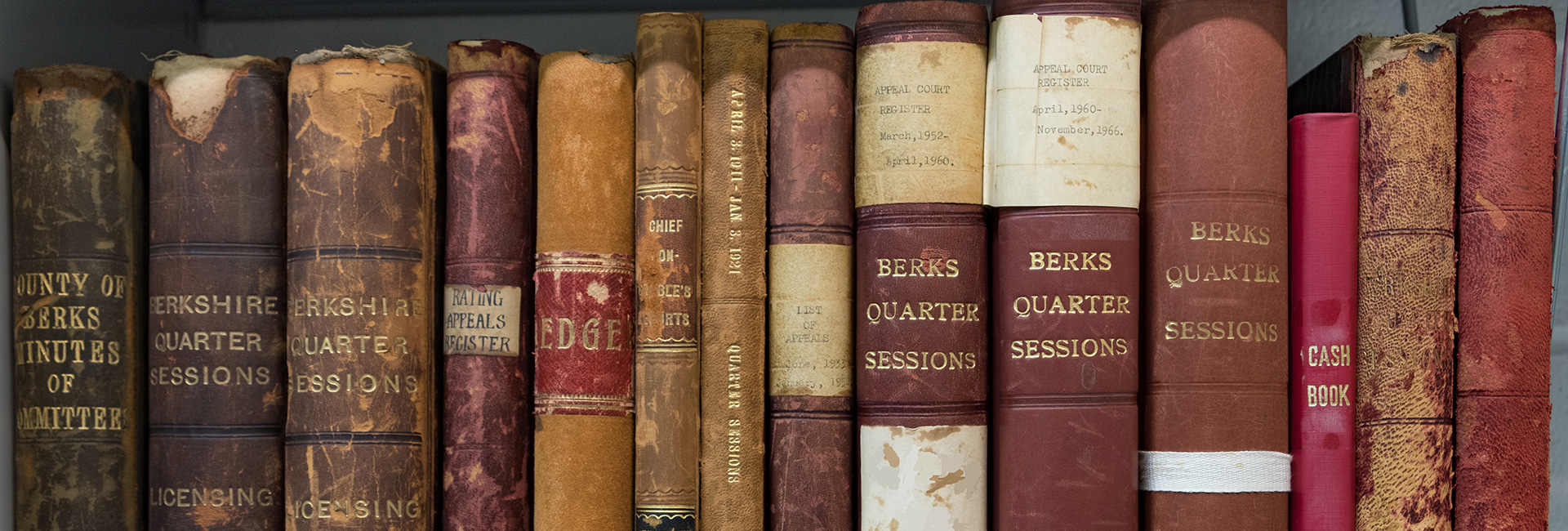

This month we are highlighting a recently purchased deed – or rather the illustrations on it!

The actual text of the deed itself is not very informative because it is a type of deed called an exemplification of a common recovery which was a kind of 'fake lawsuit'. It usually formed part of a larger series of conveyances and was processed through the Court of Common Pleas in London. The intention was to clear the title for a purchaser and ensure that anyone who might have had an interest in the property, such as the vendor’s wife, or anyone with a future interest if the property that had formed part of a settled estate (i.e. if a grandfather had entailed it on his male descendants in his will, or it had been included in a marriage settlement), was no longer able to lay claim to it in future.

Basically, the person buying the property would sue someone to whom the seller had notionally conveyed the property, saying that he/she/they had been disposed by a certain 'Hugh Hunt'. The person sued, known as the tenant to the praecipe, would then call on the actual seller to provide a warranty in court, and he/she/they would call on yet another person, known as the common vouchee. The whole thing was completely made up – and note that 'Hugh Hunt' was not a notorious fraudster dispossessing multiple landowners of their property, but was a completely invented character whose name was used in all the cases!

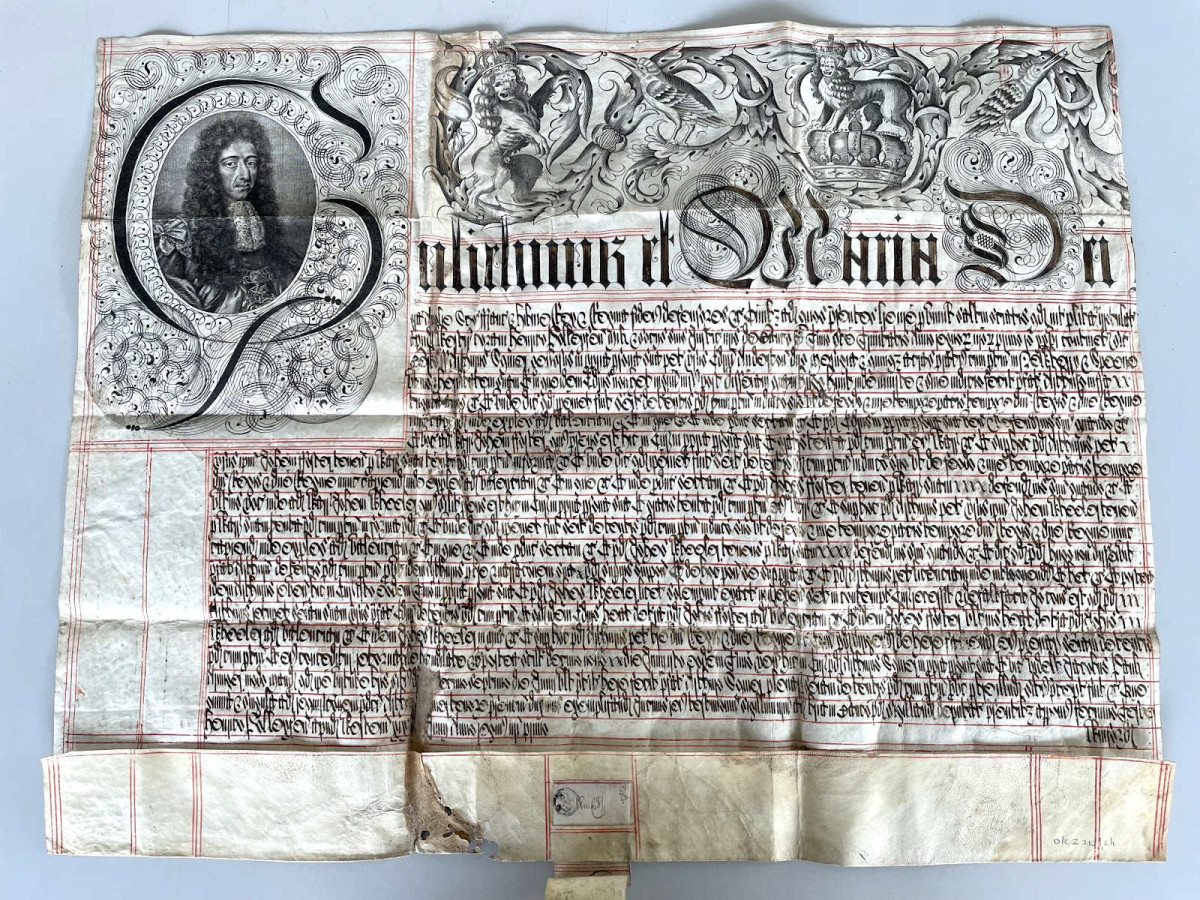

The exemplification is a large document setting out this fictitious judgement, and bears the Great Seal of the monarch, as it was his or her court, hanging from a silken rope. The seal is often stored in a round metal box called a skippet. Unfortunately, these have proved to be quite poor at keeping the seals safe, and often the seal is broken. We have a lot of these documents in the archives, as they were particularly useful for big estates. They follow a standard format, are always in Latin, and used a particular kind of handwriting which was that of the court, which can be tricky to read if you are not accustomed to it.

However, the actual content is probably of limited value to historians. They will tell you the names of the parties and wives are always included, as they could otherwise have claimed a ‘dower’ right of a third of the property in perpetuity if widowed. The description of the property is minimal, so out of context it can be difficult to tell what they relate to. Usually they will give a total number of messuages (houses), gardens, a number of acres of arable land, meadow, pasture, woodland, etc, and the parishes or manors in which the property as located, but no further information. Worse, it will not even tell you which properties are in which parish. So it might say 'three messuages, two gardens, 250 acres of arable land, 300 acres of meadow and 40 acres of woods, in the parishes of W, X, Y, and Z' - not very helpful at all.

Typically, a separate set of deeds was entered into at the same time as the exemplification which did set out the property conveyed. If these were created before the case, they are described as 'deeds to lead the use of a common recovery'; if afterwards they are described as 'deeds to declare the use of a common recovery'. The term use is another with a technical meaning in conveyancing - it meant the person with the actual beneficial interest in the property. Common recoveries were eventually abolished by the Fines and Recoveries Act in 1833.

This particular deed is for a messuage and 5 a. meadow in Newbury and Speen, dated 1689 (ref. D/EZ213/2/1), and at some point it has sadly become separated from any related deeds, so we simply do not know if the house was in Newbury or Speen, let alone exactly where it was, or how much of the land was in which parish. However, what is quite interesting about this exemplification, are the delightful illustrations.

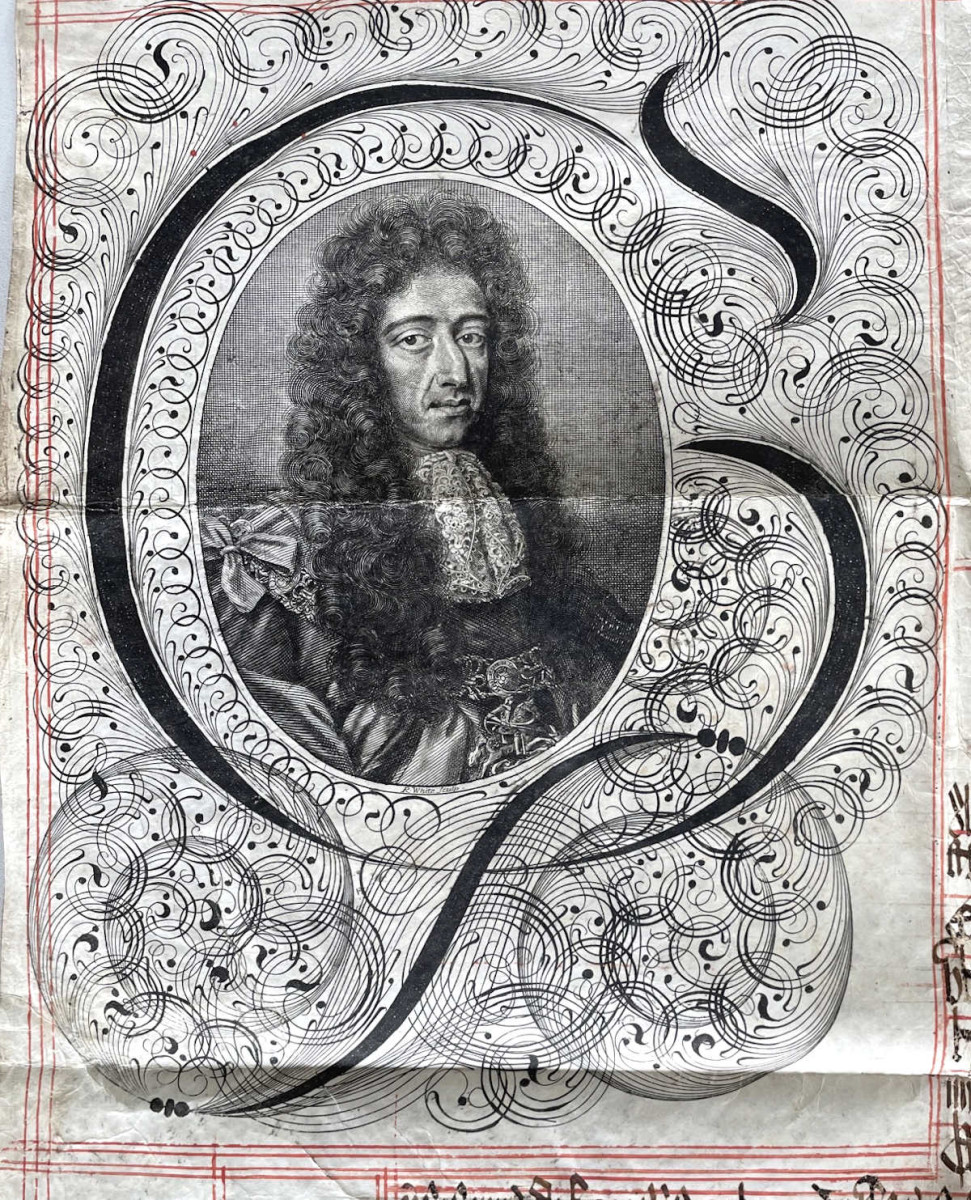

It was normal for this type of document to include a portrait of the monarch, known as a portrait initial, drawn in the first letter of their name at the start of the document. However, this is a particularly fine example, showing King William III (William II of Scotland) less than a year after his accession to the throne. The initial in question is a G, as William’s name has been translated into the Latin Gulielmus (his wife Mary is Latinized as Maria).

William III is wearing a lace jabots at his throat and has long dark curls and a ribbon on the shoulder of his outfit. You can compare this depiction with various other portraits online.

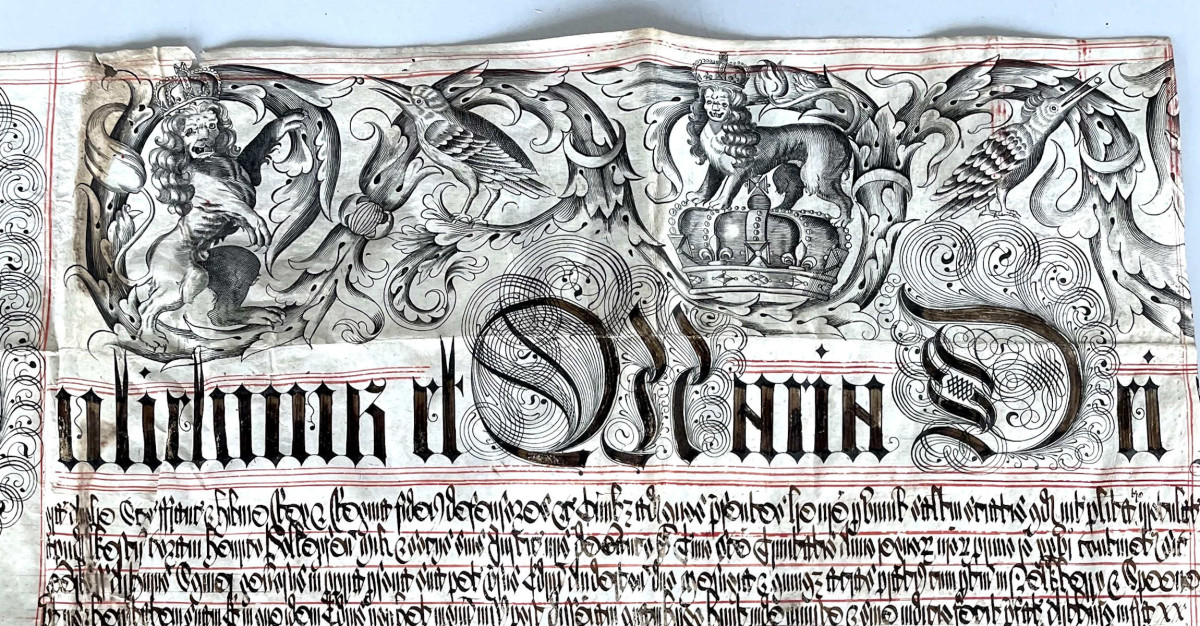

While William’s wife and co-ruler, Mary II, is not formally shown, a possibly unique aspect of this particular document appears in the decorative border. Two lions with humanized faces bearing crowns are depicted. Are these an attempt to show William and Mary perhaps?

One of the lions stands on a crown which appears to be St Edward’s Crown, made for Mary’s uncle, Charles II, in 1661. William III was the last monarch to be crowned with it until 1911 when George V brought it back into use and it is expected to be used to crown King Charles III in May 2023.

So whilst perhaps not the most useful of documents factually, the illustrations are very detailed and arguably provide an interest of their own.

Further reading:

If you would like to learn more about the crown jewels, please see the Tower of London website.