Oscar Wilde and Reading Gaol

Biographies of Wilde and Berkshire's Victorian prison

With funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with the University if Reading Department of English Literature, this exhibition was presented in autumn 2014 it was launched with a public lecture by Merlin Holland.

With funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with the University if Reading Department of English Literature, this exhibition was presented in autumn 2014 it was launched with a public lecture by Merlin Holland.

The exhibition included archives from Reading prison and rare publications by Wilde and his circle. Click n the links and display cases below to discover more about the man and the institution

Life

Oscar Wilde was born on 16 October 1854 in Dublin, to the renowned surgeon and antiquarian, Sir William Wilde, and the writer, feminist and Irish patriot, Jane Francesca "Speranza" Wilde. He graduated from Trinity college Dublin and Magdalen College Oxford with the highest honours in classical studies.

In 1879 Wilde moved to London. He became a serious and ambitious author, but he was also a flamboyant self-publicist. An inspiration to some and a joke to others, with his boldness and wit he challenged and entertained his age.

On 24 May 1884 Wilde married Constance LLoyd, a timid yet self-consciously modern woman. They had two sons, Cyril (1885-1915) and Vyvyan (1886-1967). Wilde also had sexual relationships with young men. In 1891 he befriended Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas, a reckless and destructive 21-year-old. Douglas's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, became violently opposed to the friendship. At the height of Wilde's fame, Queensberry provoked Wilde into suing him for libel. In the courtroom Wilde's private life was soon exposed. He was sentences to two years with hard labour for "acts of gross indecency with another male person." On his release, Wilde went to Europe. His health and his fortunes had been ruined by his imprisonment. He died in Paris on 30 November, 1900.

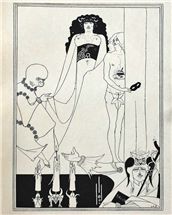

‘Salome’ UoR Coll

Wilde's early career was dedicated to poetry and drama. His poems were widely criticised as derivative, and his early plays met a similar fate. The turgid melodramas, Vera and The Duchess of Padua, were seen as “preposterous” and “long-winded.”

But Wilde soon managed to fashion a career as a writer, with reviews, stories, and essays. The stories, many of them fairy tales, were gathered in The Happy Prince and A House of Pomegranates.

Potentially shocking homoerotic and decadent elements began to feature in Wilde's writing, especially in the novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. His play, Salomé, went into production in 1892 with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role, but the Lord Chamberlain refused to grant it a licence. It was considered blasphemous to depict Biblical characters in a play.

Wilde rescued his position with a series of popular professional drawing-room dramas with a satirical edge: Lady Windermere's Fan, A Woman of No Importance, and An Ideal Husband, ending with a comic masterpiece, The Importance of Being Earnest, which was first produced in 1895.

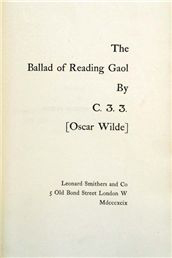

His popular and commercial triumph was brought to an abrupt end by his imprisonment. After his release he wrote the powerful Ballad of Reading Gaol, but essentially prison had killed his ambition and ended his career.

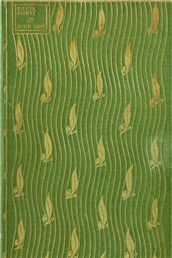

‘Silverpoints’ UoR Coll

Wilde allied himself with the tendency in the arts known as aestheticism. The aesthetes rejected what they saw as the moralism and utilitarianism of their day. They believed that art should not worry about being good or useful. Art should be beautiful. The frequently used phrase was “art for art's sake.”

Aestheticism often verged on the scandalous, and the aesthetes were frequently referred to as decadents. In France, Théophile Gautier urged l'art pour l'art in the preface to his libertine novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin. In England Walter Pater, James McNeill Whistler and Algernon Charles Swinburne disturbed Victorian sensibilities with seemingly sensual ideas in prose, painting and verse.

Wilde made it part of his aesthetic programme that books should be beautiful objects as much as readable texts. He tended toward slender, elegant volumes, instead of the long, densely-printed works of many of his contemporaries.

He and his associates were teased for offering “the tiniest rivulet of text meandering through the very largest meadow of margin.” But Wilde relished the idea of style over substance. He worked closely with others to pioneer fine publishing: artists, Aubrey Beardsley, Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, and publishers Elkin Mathews and John Lane.

Inevitably the beautiful paper, illustrations, and bindings of aesthetic publishing meant that the books could only be afforded by a small, wealthy section of society. The de luxe edition of Wilde's poem, The Sphinx (1894) was priced at five guineas. This was double what a labourer would earn in a month.

Oscar Flowers at Exhibition launch 2014

Lilies and sunflowers were emblems of the alternative art movements of the mid to late nineteenth century. These flowers often featured in the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, and they were taken up later in the century by the aesthetes or decadents.

Wilde soon established himself as the most famous or the most notorious of the aesthetes. He made lilies and sunflowers a part of his public persona, appearing in public wearing or holding them. Caricatures often made fun of his identification with the flowers, and legend sees him as the object of W. S. Gilbert's jibe in the opera, Patience:

Though the Philistines may jostle, you will rank as an apostle in the high aesthetic band,

If you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily in your medieval hand.

Later in his career, Wilde adopted a different bloom, the green carnation. The Star reported seeing him at an opening night with “a suite of young gentlemen all wearing the vivid dyed carnation which has superseded the lily and the sunflower.” Robert Hichens wrote a novel satirising the aesthetes, The Green Carnation. The central character, Esmé Amarinth, is a thinly disguised version of Wilde.

Nowadays there are numerous varieties of green carnation. In Wilde's day, a green carnation was produced by spraying a white carnation with dye.

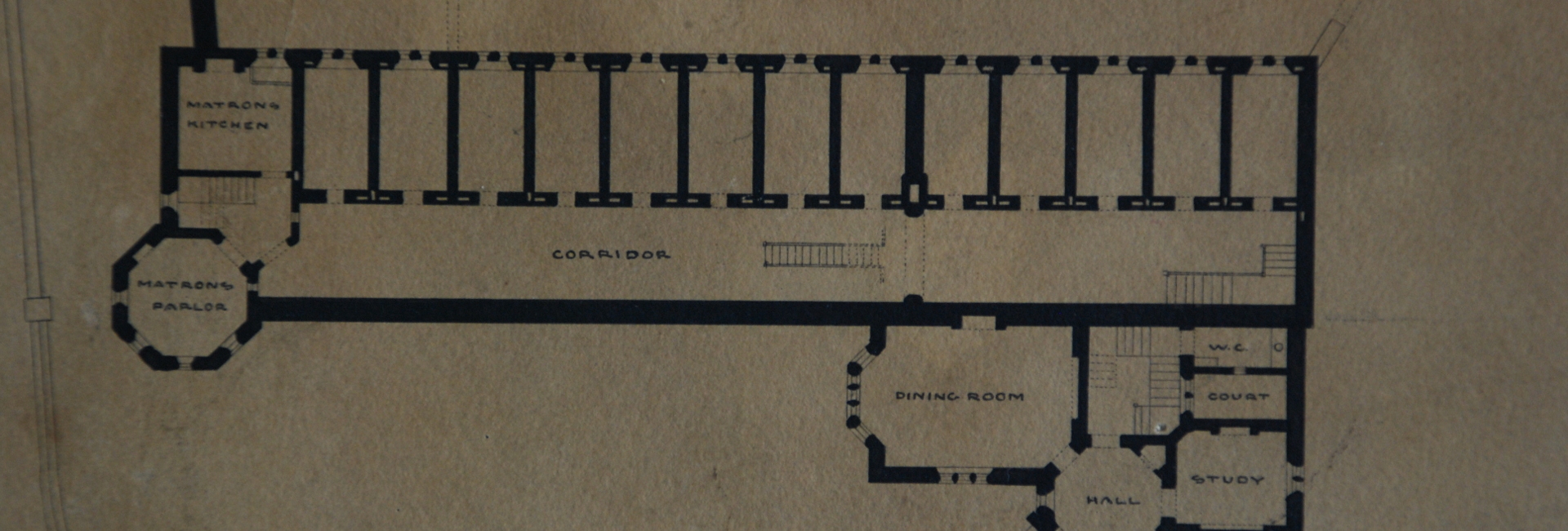

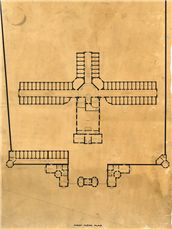

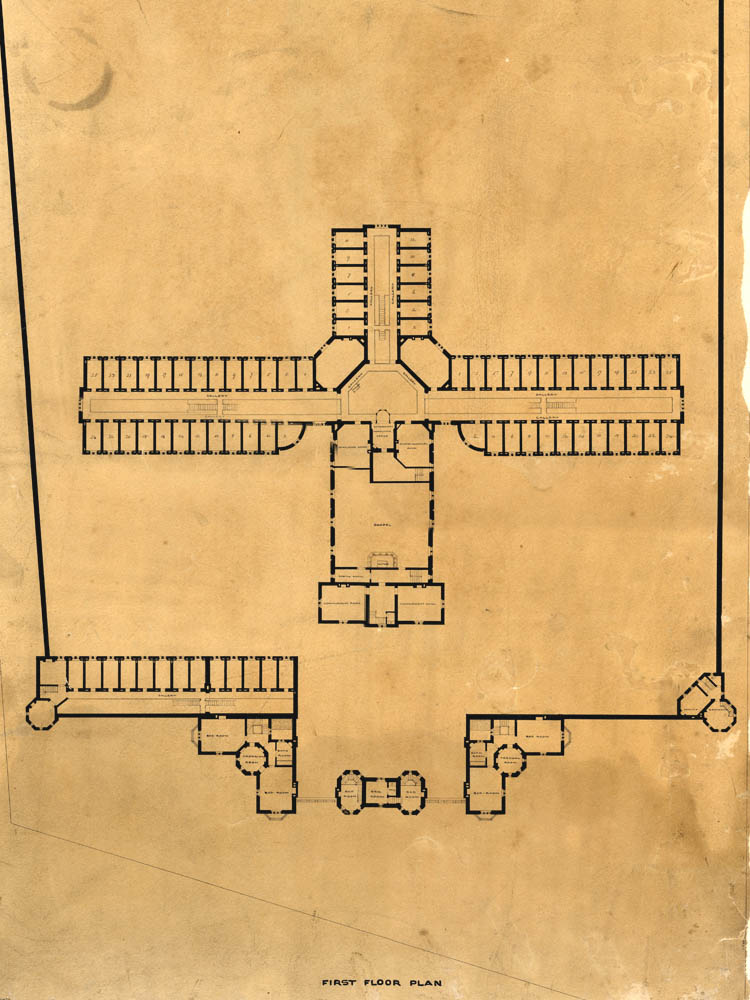

Plan of Reading Gaol 1842

The first “house of correction” on the Forbury site was built by the Berkshire justices in 1785. It had a communal dayroom and dormitories, with no plumbing or sanitation, but a treadmill for grinding wheat and an ornamental garden

In December 1841, the justices received a letter from Home Secretary Sir James Graham which criticised their gaol. It did not conform to new regulations: male and female prisoners could see and talk to each other; no reception or punishment cells were available; and there was not enough room for all prisoners to attend chapel.

The Justices decided that the only way to address these defects was to build a new gaol.

Work began in late summer 1842 and continued for nearly two years.

The new building was based on the 'model prison' at Pentonville. It was designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and William Bonython Moffatt.

It was constructed to hold 200 male criminals in three wings, and a handful of bankrupt debtors in a fourth wing. A separate room for to block for 25 female criminals was built in the north east corner of the site.

Reading Gaol was declared open for business on 1 July 1844.

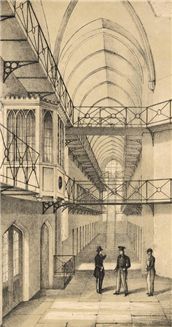

In contrast to the old gaol, the Berkshire justices ran the new prison on the “separate system”. This defined a regime

So as to permit of no communication whatever; the observance of perfect silence except between the prisoner and the officers of the gaol; religious and other instruction judiciously administered.

Prisoners stayed in their single cell, measuring 13ft x 7ft, virtually all day. They were permitted out only to exercise, clean the wings or attend chapel. At such times the male prisoners wore peaked caps to prevent them looking upwards, while the women wore veils.

Within each cell, prisoners had a basin, toilet and running water. In the day they sat on a stool at a fixed table, reading or learning to read; at night, they slept in a hammock.

However, the separate system soon became unfashionable. By the 1860s, prisoners had begun to work together in hard labour: milling wheat by hand for prison bread, or breaking stones to sell for road building. The cell plumbing was stripped out, and the hammocks replaced with wooden planks.

Throughout the Victorian period prisoners wore a brown cloth outfit in either child or adult size. The prisoners were given three meals a day of bread and water, gruel (oatmeal boiled in water), or potatoes.

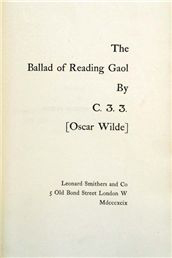

‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’ UoR Coll

Oscar Wilde arrived in Reading Gaol on 20 November 1895. He joined 133 other men in custody and was allocated cell C3.3, on the first floor landing, south side of C wing.

By 1895, the gaol had passed from the justices' control to the Home Office. Prisoners were still expected to be silent and study scripture, and oakum picking - teasing apart strands of tarred rope - had become the principal form of hard labour.

Initially subject to this regime, Wilde was eventually relieved of hard labour and allowed access to books. However, his health and morale had been badly damaged and he never fully recovered. Given pens and paper, he wrote the letter De Profundis about his plight.

Wilde was greatly affected too by the people he encountered, and several of them feature in his prison writings . CharlesThomas Wooldridge is probably the best known. The trooper at the heart of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Wooldridge was hanged at

Reading in July 1896 for the murder of his wife, Ellen. Wilde's poem is dedicated to him.

Wilde was discharged from Reading on 18 May 1897. A year later, the Prisons Act abolished hard labour and lifted the insistence on silence in gaols.

Onward we go to find more content

Just a bit more

The final tab