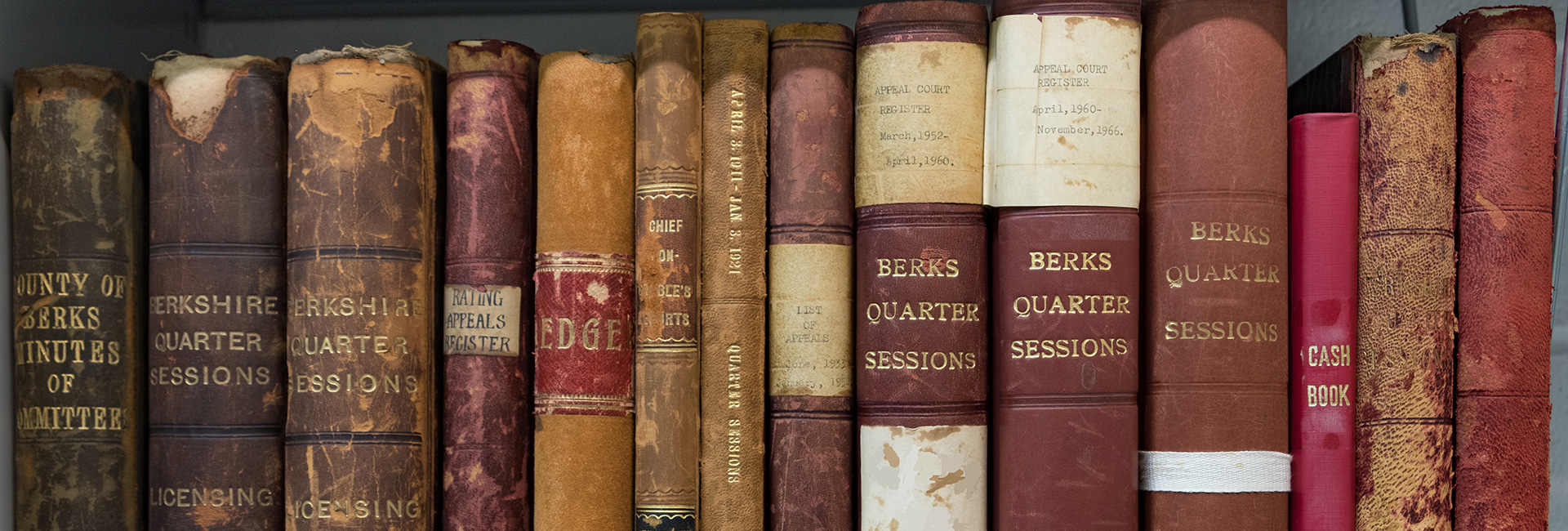

Following the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834, the Poor Law Commission was established to oversee the action taken by local authorities. These local authorities were Boards of Guardians who each had their own workhouse to run. Berkshire had twelve of these boards (Abingdon, Bradfield, Easthampstead, Faringdon, Hungerford, Maidenhead (formerly Cookham), Newbury, Reading, Wallingford, Windsor, Wokingham and Wantage). Our focus today is on the Bradfield Board of Guardians and the disagreements that they had with the Poor Law Commissioners in 1844. This is recorded within the Minutes book of the Boards of Guardians (G/B1/13).

Early in the year, the Clerk of the Board and Master of the Bradfield Workhouse, Mr Thomas Beale, passed away and there was a need to appoint a new person to the role. On the recommendation of the Poor Law Commissioners, the post was split in to two roles. It was noted in the minutes that the Board took this decision in the absence of Mr Hopkins, something which may not seem relevant until later in the tale. The son of Mr Beale, who had been filling in for his father in the interim, was appointed as Clerk making this a relatively simple appointment compared to what would follow.

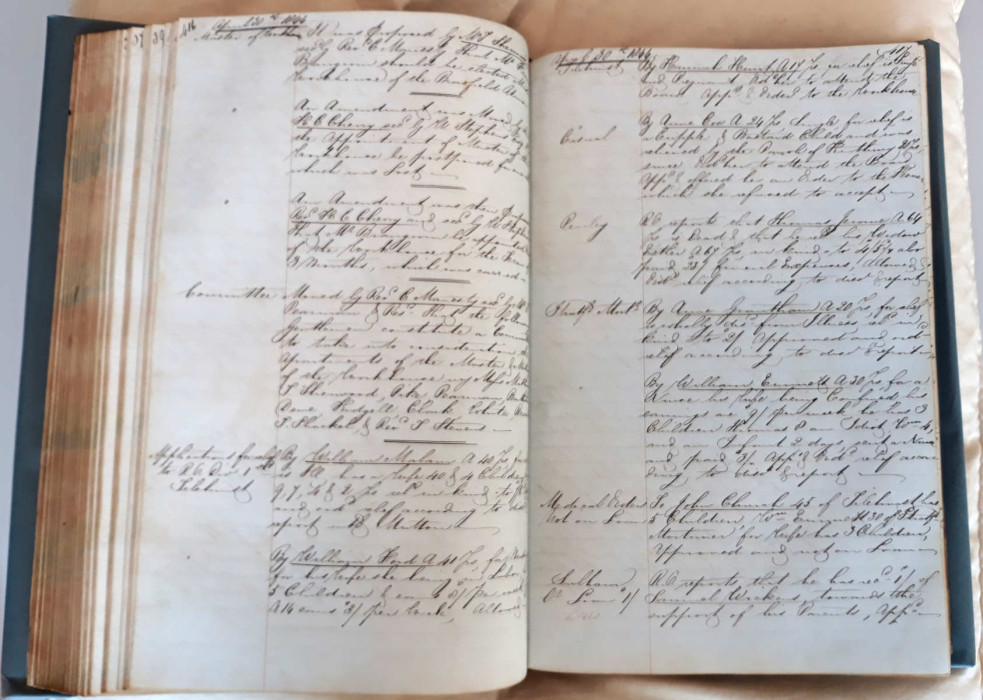

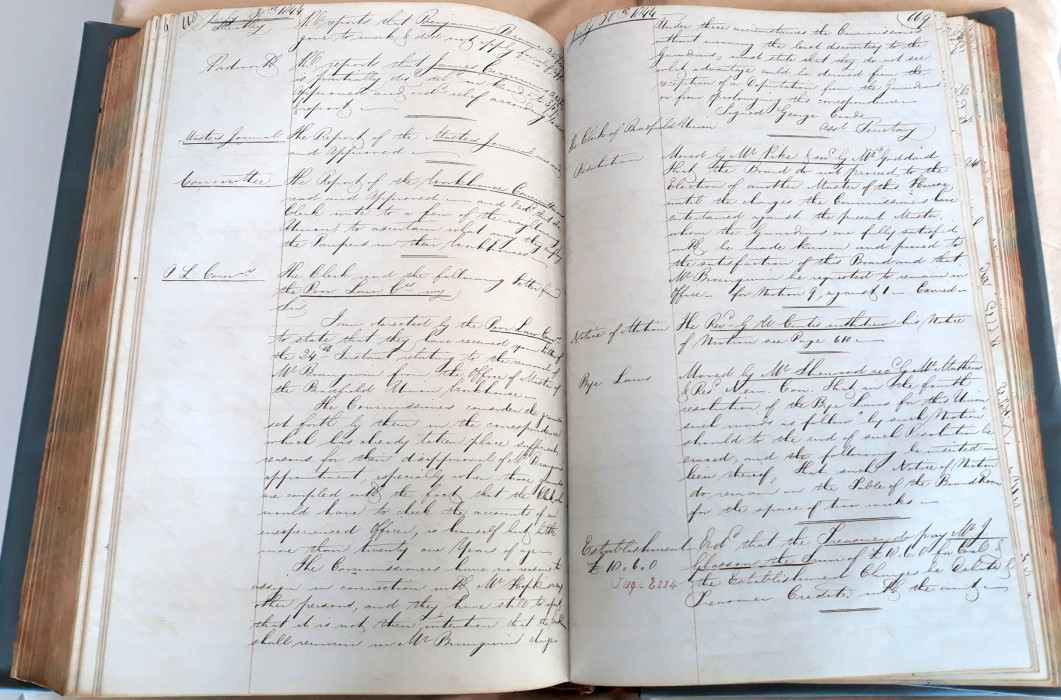

In the same meeting on April 30th 1844, the Board passed several motions. The appointment of the Master of the Workhouse would be postponed for one month, the appointment would be for a term of three months, and most importantly, Mr Francis Brangwin was appointed as Master of the Bradfield Workhouse. Two weeks later, the Board received a letter from the Poor Law Commissioners expressing their concerns about the appointment. They complained that Mr Brangwin had recently been bankrupt and had a number of outstanding affairs that had yet to be settled. Using these factors as their reasoning, the Commissioners refused to sanction the appointment and instead encouraged the Guardians to proceed with electing an alternative candidate.

The Guardians responded to this by assuring the Commissioners that they were satisfied with the appointment of Mr Brangwin and that his affairs had been settled in August 1843. It is here that the Guardians first appear frustrated with the Commissioners as they refuse the request to appoint a different Master and accuse the Commissioners of soliciting advice from a private source who the Guardians believe has provided false information about Mr Brangwin, something of which “the Board highly disapproves”.

The response from the Commissioners offered a clarification of their initial decision. They admitted that their use of the word ‘unsettled’ may have been unfair, but again raised the concern that Mr Brangwin’s debts were outstanding despite what the Guardians had claimed. They raised a further concern, namely that Mr Brangwin did not possess enough experience in a related office in their view. Again, they requested for the Guardians to make a new appointment.

One member of the Board of Guardians, and seemingly a staunch supporter of Mr Brangwin, was Mr Sherwood, and it was he who moved the response to the Commissioners. The Board confirmed again that they did not regret the appointment of Mr Brangwin and that their mind had not been changed by the Commissioners’ letter. The response takes on a slightly conspiratorial tone when they again suggest that the Commissioners are taking private advice, this time accusing their source of actively working against the Board.

A further twist arises when it is revealed that Mr Brangwin was himself a member of the Board of Guardians for five years, the Guardians arguing that he would therefore have the relevant knowledge to fulfil the duties of Master of the Workhouse. The Board also raise the level of inflammatory language, accusing the Commissioners of “dire oppression” in disqualifying Mr Brangwin from the office.

They also responded with a copy of a letter from the trustees of Mr Brangwin’s estate. The letter was signed by J Stephens, J Swallow and W Deacon, and stated that his creditors have been paid and that they considered him to be “an honest man”.

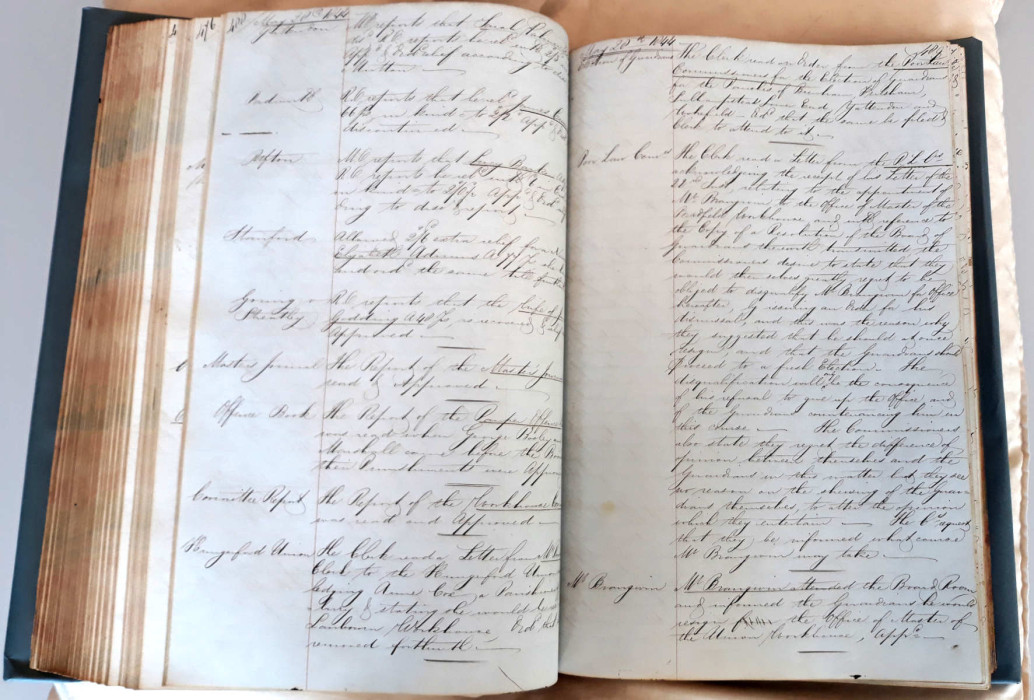

A week later, the Commissioners responded again, this time saying that they were not disqualifying Mr Brangwin from future offices but encouraged him to resign. Future disqualification would arise in consequence of his refusal to resign, something they make clear that they would order if necessary. They do show some regret at the difference of opinion, but at the same time show no signs of acquiescing to the Board of Guardians. Mr Brangwin himself attended the board room for this meeting, and informed the Board that he would resign from the office. This was accepted, and notice was given for a motion to elect a new Master at a future meeting.

Mr Sherwood expressed his dissatisfaction with the Commissioners decision as follows:

“Moved by Mr Sherwood and sec[onde]d by Mr H White that this Board cannot avoid expressing their sentiments of contempt at the course adopted by the Poor Law Commissioners in compelling the resignation of Mr Brangwin after being unanimously elected by this Board who are certainly the most competent judges of his fitness. The Board of Guardians also consider that the tyrannical conduct of the Poor Law Commissioners in this respect is not calculated to lead to any favourable view of Justice in the exercise of their power and furthermore likely to impair the future efficiency of this Board in the discharge of their duties”.

Eight members of the Board were for this motion, with only one opposing.

Despite the inflammatory language and clear dissatisfaction of most of the board, this appeared to be the end of the conflict. The Board received a letter of resignation from Mr Brangwin on May 29th and proceeded with the motion for a new appointment in the June 11th meeting. However, the disagreements were only just beginning.

On June 18th, the Commissioners sent a further letter to the Board of Guardians revealing that Mr Brangwin had been re-appointed as Master of the Workhouse. This was clearly against the wishes of the Commissioners and resulted in them ordering the dismissal of Mr Brangwin from the office. They lay the blame for this order at the feet of the Board and Mr Brangwin himself due to their persistence in resisting the Board’s advice. Once again, the Board was given notice that a move to appoint a new Master would be made at a future meeting.

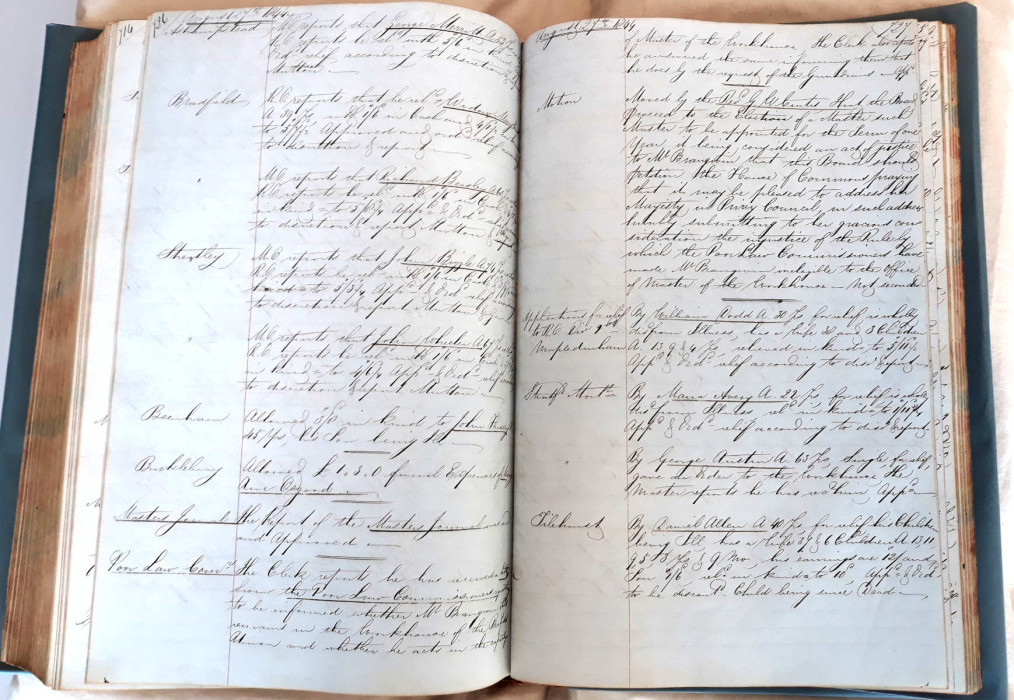

The next week, the Commissioners acknowledged the Guardians’ decision to disregard their orders but remained firm in their position. They write that the order for Mr Brangwin to leave the workhouse does not come into effect until July 2nd, fourteen days after the order was given. They then demand to be told on July 3rd whether Mr Brangwin has vacated the office and warn that he will be subject to penalties should he remain.

At the following meeting, on the day that Mr Brangwin was ordered to have left the office by, Mr Sherwood presented to the Board a letter that he had received from Robert Palmer, MP for Berkshire. Interestingly, before it could be read, it was moved by Mr Hopkins that the Officers of the Union who were present should leave the room. Mr Hopkins’ reasons for this become clear with the contents of the letter. This movement was rejected, and it was overwhelmingly supported that they should stay.

The contents of Mr Palmer’s letter are very interesting and add a new wrinkle to the saga of Mr Brangwin. Mr Palmer refers to correspondence he had with Mr Hopkins, presumably the same Mr Hopkins who is on the Board. In the said correspondence, Mr Hopkins allegedly states several reasons why he considers Mr Brangwin to be an unfit appointment as Master of the Workhouse. This is initially surprising as previous entries in the minute book stated that the appointment of Mr Brangwin was a unanimous decision, but it is worth noting that it was Mr Hopkins who was absent during the meeting where Mr Brangwin was appointed. Mr Palmer agrees with the Board that there appear to be reasons that the Commissioners object on beyond what is described in their letters. He ends the letter by recommending that the Board talk to Mr Hopkins on his reasons for his disapproval of Mr Brangwin.

This letter certainly shook things up in the Board and led to the postponement of appointing a new Master. The implication from this meeting was that a member of the Board had gone behind the backs of his fellow Guardians to discourage the Commissioners from approving the appointment of Mr Brangwin. The Board moved that until the member in question had proven his misgivings to be well founded, then they would not move forward with the appointment of a Master.

At the same meeting, a letter from Mr Brangwin was read, in which he again requested leave to resign his post and described himself as ‘a poor defenceless man’, giving the impression that he was being picked on by a more powerful body, namely the Poor Law Commissioners. However, in this letter, Mr Brangwin also offered to continue carrying out the duties until the Board elected a new Master. Given the previous resolution to postpone this decision, this seemed like a way for Mr Brangwin to continue in the office for some time. This offer was, unsurprisingly, accepted by the Board.

By the meeting on 9th July, the Commissioners were aware of Mr Brangwin’s offer and did not appear pleased by it. They felt that it was not proper to leave a man they deemed unfit in the Office for the interim period even if it left the Workhouse with no Master. Both the Guardians and Mr Brangwin were warned that, should he continue to reside in the Office of Master, he would not be paid for services tendered and may open himself to more serious repercussions. To the Commissioners’ credit, they gave Mr Brangwin the benefit of the doubt in this case, suggesting that the Board had not made him aware of the seriousness of his situation.

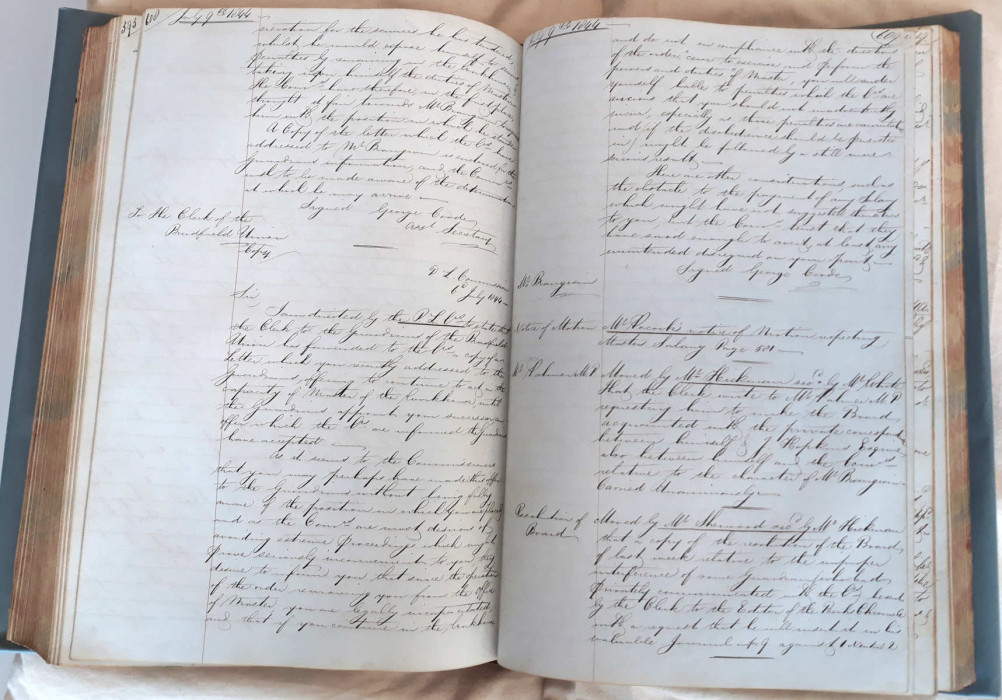

In response to this, Mr Sherwood moved that the Board take steps to publish the resolution made the previous week in the Berkshire Chronicle by contacting the editor. The Clerk was also ordered to write to Mr Palmer and request further details of his correspondence with Mr Hopkins. Both these motions were carried.

It is at this point, as hostilities between parties seemed to be increasing, that one member of the Board made an attempt at playing peacemaker. The Reverend Curtis advised his fellow Guardians that he would be proposing several resolutions intended to avoid similar future complications. These included any misdeeds by a Guardian being brought to the board, rather than censured by an individual; not allowing Guardians to get professional persons advice on Board matters; and not allowing publication of the Boards correspondence and business in the press unless agreed by all members. Whether these resolutions had the desired effect is unclear.

The response from Mr Palmer was read the following week. In it, he clarifies that he has already provided Mr Sherwood with everything he is willing to divulge in the previous correspondence. He refers the Board to Mr Hopkins for more details, but also mentions that he understands Mr Hopkins has refused to speak with the Board when requested. Without his permission, Mr Palmer refuses to offer a transcript of the letter he received from Mr Hopkins. This is seemingly the end of Mr Palmer’s involvement with this case.

On 23rd July, we get the first recorded meeting between the Board and the Commissioners with regards to Mr Brangwin’s status. It is written that Mr Brangwin received a request from Mr Parker, the Assistant Commissioner, to meet outside St Mary’s Workhouse in Reading. Mr Brangwin was accompanied by one of the Guardians, and they were informed by Mr Parker that he had been instructed to remove Mr Brangwin from Office “by the strong arm of the law”. In response to this, the Guardians reiterated their complaints that the Commissioners were treating Mr Brangwin unfairly and that they must have had other grounds for their disapproval. They show how they have attempted to find what these other grounds of disapproval were and also claim that the Commissioners have previously sanctioned officers who were insolvent. They say that they can prove such appointments took place, but do not offer any evidence at this time. Finally, they offer to have the Commissioners conduct a strict investigation of Mr Brangwin’s character, so that either the Board or the Commissioners can be proved right once and for all.

Despite this offer, the Commissioners declined, stating that they could see no benefit to such an exercise. For the first time in quite a while, they do briefly expand on their reasoning, as they state that the accounts of an inexperienced officer (i.e. Mr Brangwin) would have to be checked by the Clerk, whom they also seem to consider inexperienced. There is some logic to this, as the Clerk was appointed only briefly before the issues between Board and Commissioners began.

Two weeks later, the Board was attended by the aforesaid Mr Parker. He informed them that he had been instructed to begin proceedings against Mr Brangwin, but had come to advise the Board against continuing on their current course of action. Interestingly, it is noted that his doing this was not authorised by the Commissioners, and he seems to have done it of his own initiative.

It seems as though this advice was not heeded as Mr Brangwin was brought before the Magistrates for disobedience to the Commissioners’ orders. He was found guilty, but fined the minimum amount of one farthing. Following this, the Board again began to move towards appointing a new Master of the Workhouse, but were not going to do this quietly. They moved to petition the House of Commons to address the Queen in Privy Council to inform her of the situation and complain of the seeming injustice done by the Poor Law Commissioners.

It would be about three weeks before the next correspondence between the Board and Commissioners. The Commissioners simply asked whether Mr Brangwin was still presiding over the Workhouse, to which the Board responded that he was at their request. This would prompt the next steps about two weeks later.

On 10th September, the Commissioners wrote again expressing displeasure that Mr Brangwin was still in the office of Master of the Workhouse. As a result, they felt that they had to begin proceedings towards a second conviction of Mr Brangwin, and ordered the Board to proceed to a new election. They end the letter by saying that they are only acting with the best intentions for the Workhouse, whilst also implying that they will bring proceedings against the Board too, should they ignore the Commissioners’ order.

This leads to the final response from the Board to the Commissioners on this matter, and it is the most strongly worded of all. In the two page response, the Board deny the Commissioners’ claim that they feel regret in their prosecution of Mr Brangwin, and disparage the implication that they should have left the Workhouse without supervision by a Master. They describe the Commissioners’ approach to the situation as “tyrannical”, “unconstitutional”, and “unEnglish”. They close their letter with the hope that public exposure of this case would lead to legislation being passed “against evils so glaring and so indisputable”.

This seemingly brings to the end the saga of Mr Brangwin and the dispute that rose out of it. Despite all the twists and turns, this series of events only lasted for around five months yet dragged many different individuals in. The strong wording in the letters show how deep the animosity between the two sides was by September, but presumably they found a way to continue working together.

The Royal Berkshire Archives holds records for each of the 12 Poor Law Unions of Berkshire, including minute books, relief lists, and more. To find out more about these collections, please see our online catalogue.