Reading Abbey 900: Collections at Royal Berkshire Archive

2021 marks 900 years of the founding of Reading Abbey. The items displayed on this page have been put together by the RBA in collaboration with the History Department of the University of Reading. They relate to what happened after the Abbey was dissolved following Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries, and provide a detailed description of each item.

To enlarge individual images, you can right click on the image, select 'open image in a new tab' and use the zoom function. Alternatively, use your browser's zoom function.

After the Abbey

The relationship between town and abbey came to a sudden end in 1539. Sensing imminent threat, Abbot Hugh Cook had made Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister, life-steward of the abbey. But this did not prevent the former’s trial for high treason.

After the execution of the abbot and two other clerics, the suppression of the monastery and the partial demolition of the church, Cromwell was established as High Steward of the re-organised borough. As the Diary of the Corporation of Reading noted: ‘After this suppression all things remain in the hand of the lord king’. Henry retained part of the abbey buildings for royal use, which became known as the ‘first mansion of Reading’. The documents in this section show the gradual handover of abbey resources and responsibilities from the crown to the officials of the borough.

Henry VIII

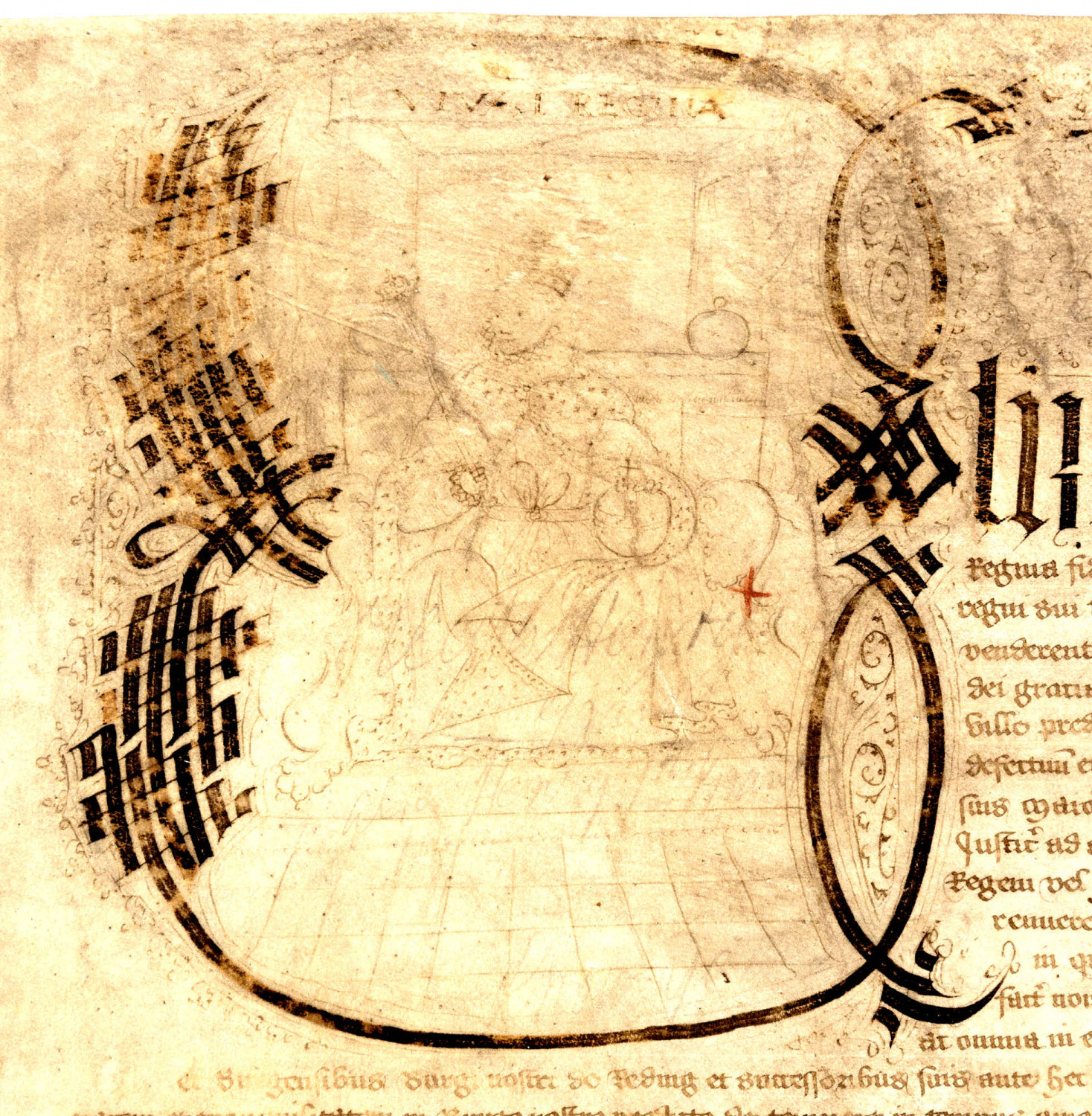

R/IC1/6 - Portrait initial of Henry VIII

Portrait initial of Henry VIII, from his charter to Reading borough, 1542. This revised portrait can be compared with that of 1520. The coloured portrait initial shows Henry seated on his throne, with the mayor and burgesses kneeling before him.

This charter, the first after the Dissolution, of the Abbey, passed on some rights to the town. It gave the buildings of the other religious order based in Reading, the Franciscans (also known as the Grey Friars) including Greyfriars Church, to use for building work on the gildhall.

The town also received the right to hold assizes of bread, wine and beer, previously controlled by Reading Abbey. However, the profits of fairs held in the town were given to royal servants, who also received most of the abbey properties in the town.

The abbey itself remained in royal hands in the reigns of Edward VI and Mary, and records at the National Archives show the impressive quantities of materials and wealth removed. There is evidence that the burgesses of Reading found this a difficult period and that the wealth of the town temporarily declined. However, the reign of Elizabeth I changed things.

Elizabeth I

R/IC1/8 - Portrait initial of Elizabeth I

Portrait initial of Elizabeth I, from her charter to Reading borough, 1560.

This portrait shows Elizabeth, who only became queen in November 1558, as a young woman, confidently displaying all the regalia associated with the monarchy. She looks directly at the viewer in a manner which conveys assurance. The portrait is skilfully drawn and economical in its use of line. It appears to be based on the image known as the Coronation Miniature, painted by the court painter, Nicholas Hilliard, and now lost. This was the new queen’s official ‘face mask’ in the first part of her reign and was used also in her first seal. A miniature in the collection of Welbeck Abbey provides a good example of this royal image.

One of the most important grants to the borough of Reading, the charter set out the borough boundaries and gave the borough many more rights formerly appertaining to the abbey. Provisions included appointment of the mayor as clerk of the market, the right to hold a court of quarter sessions (for criminal offences), a court leet (for minor offences), and court of pie powder (held during fairs and markets), and to have a weekly market and four fairs per year.

Even more significantly, the Mayor and burgesses were given rents from more than 300 properties in the town, once belonging to the abbey and recently held by royal appointees. And perhaps most importantly, Sir Francis Englefield, who had been made ‘keeper’ of the borough by Queen Mary, now fell from power, and all his rents were transferred to the Mayor and burgesses. The borough was also allowed the use of stones from the abbey ruins to repair the town's bridges, and the right to appoint the master of the grammar school.

Official images of Elizabeth I held elsewhere

While the Darnley Portrait is believed to have been painted from life, the Reading one has features which are less clearly defined. However, the Reading portrait shows Elizabeth I wearing a white satin ‘doublet’ which is probably that given to her by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Moreover, the style of this portrait is very close to the portrait of Leicester which is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

This evidence strongly suggests that the portrait is one of a set commissioned by Leicester in 1575 for the famous visit by the queen to Kenilworth House. How it came into the possession of the Borough of Reading is not known. The queen herself visited Reading a number of times and retained possession of the site of the abbey and all remaining buildings and materials, although all but the royal stables were leased to Richard Okeham from 1570. By 1650 the former royal residence was made up of an impressive group of buildings and gardens, including the inner gateway, occupying at least two acres; but there is no mention of paintings.

R/IC4/1 - Grant of arms

Grant of arms to the borough of Reading, 1566.

The first formal grant of arms to Reading. One school of thought is that the five mysterious heads are supposed to be Queen Elizabeth I and four of her ladies in waiting. This is possible, although the heads predate her reign and can be traced back to at least the 14th century. The letters RE stand for Regina Elizabeth (Queen Elizabeth). The staining is the result of varnishing in the late 19th or early 20th century.

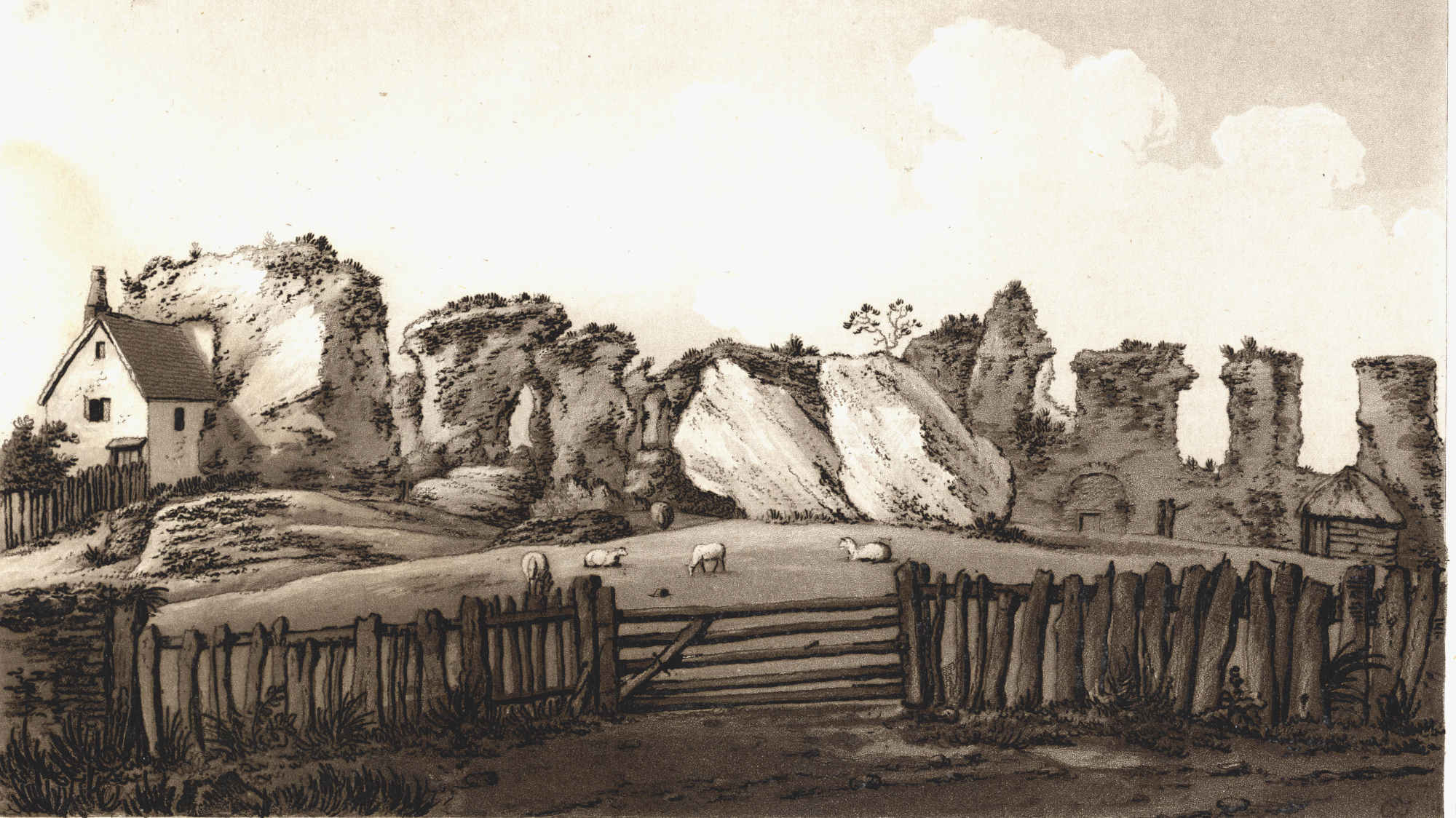

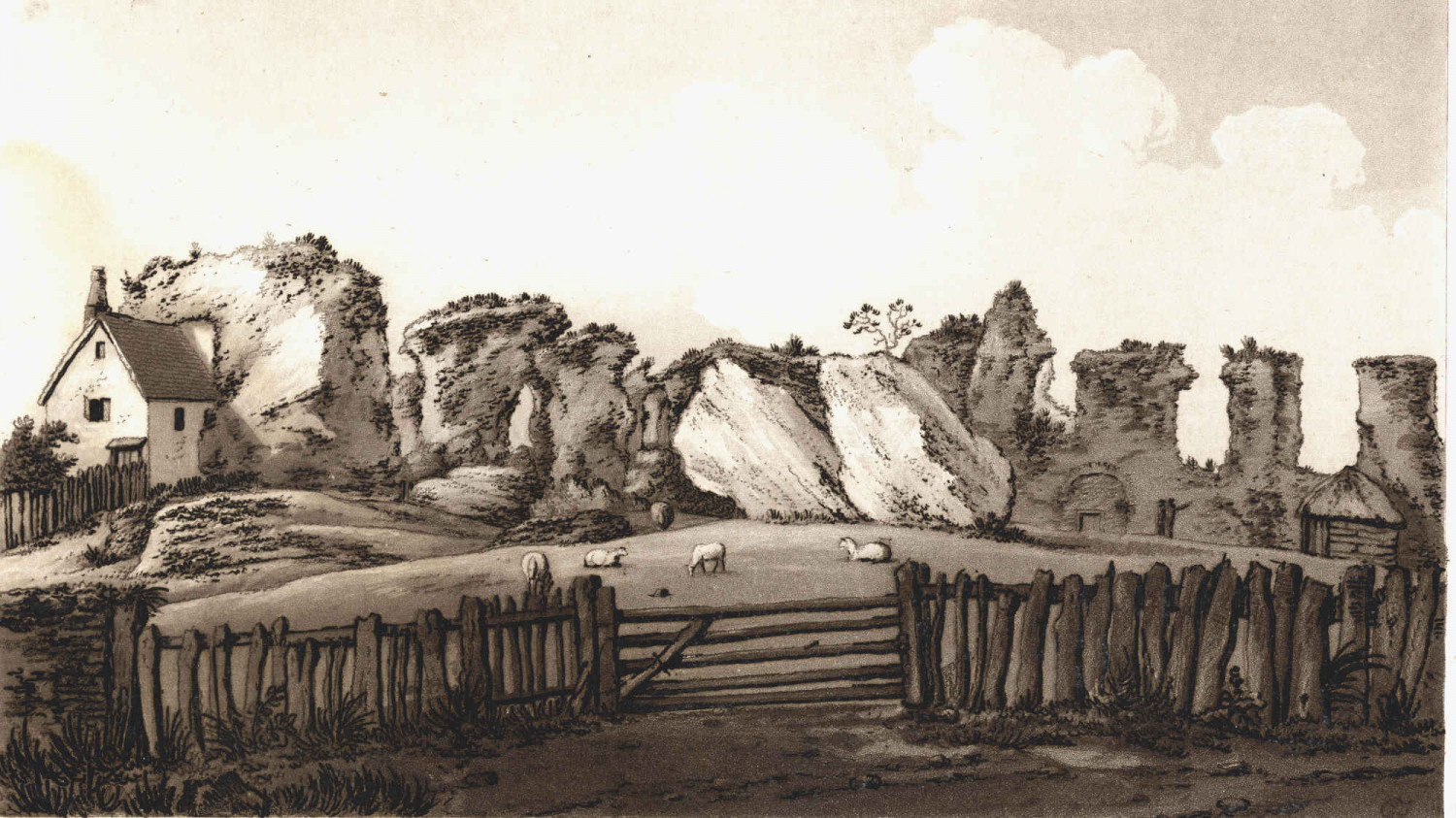

D/EX27/Z8 - Print of Abbey ruins

Print, entitled ‘North view of the ruins of Reading Abbey’, found in a collection of similar views, shows sheep grazing undisturbed in the grounds in c.1800.

Artists and antiquarians of the 18th and 19th centuries found monastic ruins a romantic subject. and many sketches were made of the abbey's remaining stones.

D/EX2807/37/11 - Print of the Abbey Gateway

Print of the Abbey Gateway, 1775.

Entitled ‘A South Prospect of the Abby-Gate [sic] at Reading', by Michael Angelo Rooker (c.1743-1801) after a drawing by Paul Sandby (1731-1809).

This depiction of the instantly recognisable Abbey Gateway (still standing today) would have found a wide circulation. It was sold as a standalone print, and was also published in the periodical The Copper Plate Magazine in 1778.

You can go back to the Reading Abbey page or go back to Part One: Living with the Abbey.

For current information about the Reading Abbey ruins, visit the Reading Abbey Quarter website.