Reading Abbey 900: Collections at Royal Berkshire Archive

2021 marks 900 years of the founding of Reading Abbey. The items displayed on this page have been put together by the RBA in collaboration with the History Department of the University of Reading. They relate to living with the Abbey and provide a detailed description of each item.

Once you've finished this page, click through to Part Two: After the Abbey to find out more.

To enlarge individual images, you can right click on the image, select 'open image in a new tab' and use the zoom function. Alternatively, use your browser's zoom function.

Living with the Abbey

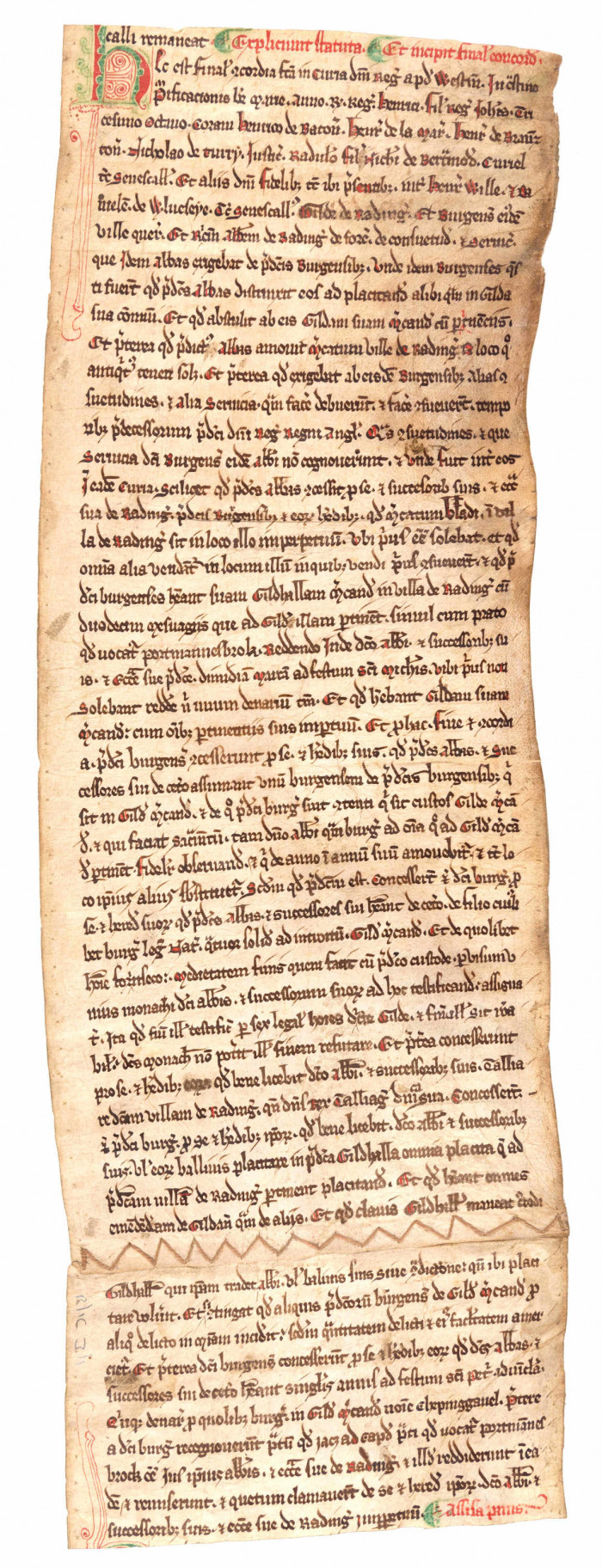

R/IC3/1 - Copy of agreement

This is the copy of agreement in the king's court at Westminster (final concord) between Henry Wille and Daniel Wolveseye, stewards of Reading gild, and the burgesses of the town, and Richard, Abbot of Reading, dated the morrow of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary [3 February], 38 Henry III [1254].

This agreement was intended to resolve a long-running dispute between the abbey and the gild members. In February 1253 Reading burgesses had to explain to the king why they had violently resisted the abbot’s officers. Five months later, the gild paid the very high sum of £100 for a royal charter granting freedom to trade across England – but not freedom from the control of the abbey. This agreement of 1254 sets out the future rules of engagement between the two bodies.

The abbot conceded the burgesses' right to hold a corn market in the town, and to sell such other goods as were customarily sold there. He also granted possession of the gildhall and twelve messuages (houses) belonging to it, and a meadow called Portmanbrook ('Portmannesbrok'), for an annual rent of half a mark, paid at Michaelmas. This meadow was an important resource, and the right to keep cows grazing on it was claimed by the burgesses up to the suppression of the abbey.

The burgesses conceded that the abbot and his successors should pick one of the burgesses each year to be warden ('custos') of the gild merchant. This man was effectively the forerunner of the town mayor. The abbot received 4s from every legitimate son of a burgess admitted to the gild, and half the admission fine for any ‘foreigner’ (i.e. any person from outside Reading). This fine was assessed by the warden and a monk from the abbey, and witnessed by six lawful men of the gild. Each burgess in the gild also had to pay the abbot 5d annually on St Peter's day (29 June) under the name of 'chepyngavel' for the right to trade in the town (Chepyng comes from an Old English word meaning market).

In addition the abbot retained the right to levy tallage (a form of tax) in the town whenever the king levied tallage in his estates. Another major victory for the abbot was that his bailiff should preside over the town court in the gildhall, to hear all pleas relating to the town, whether cases involved the gild members or others. And while the key of the gildhall remained in the custody of its wardens, they had to deliver it to the abbot or his bailiff when they wished to hear pleas.

Finally, the burgesses accepted that the meadow lying at the head of Portmanbrook belonged to the abbot, and gave up their own claim to it.

The document is in Latin, which was the standard legal language until 1733.

The original agreement was enrolled at the royal courts, following a lengthy and contentious dispute which allegedly included an incident when Reading men ‘lay in wait’ for the bailiffs and servants of the abbot, and attacked them with weapons. This copy is on two sheets of parchment stitched together, with prayers and a religious poem (in French) on the other side. The sheets appear to have been cut from a statute roll or cartulary, possibly belonging to the abbey.

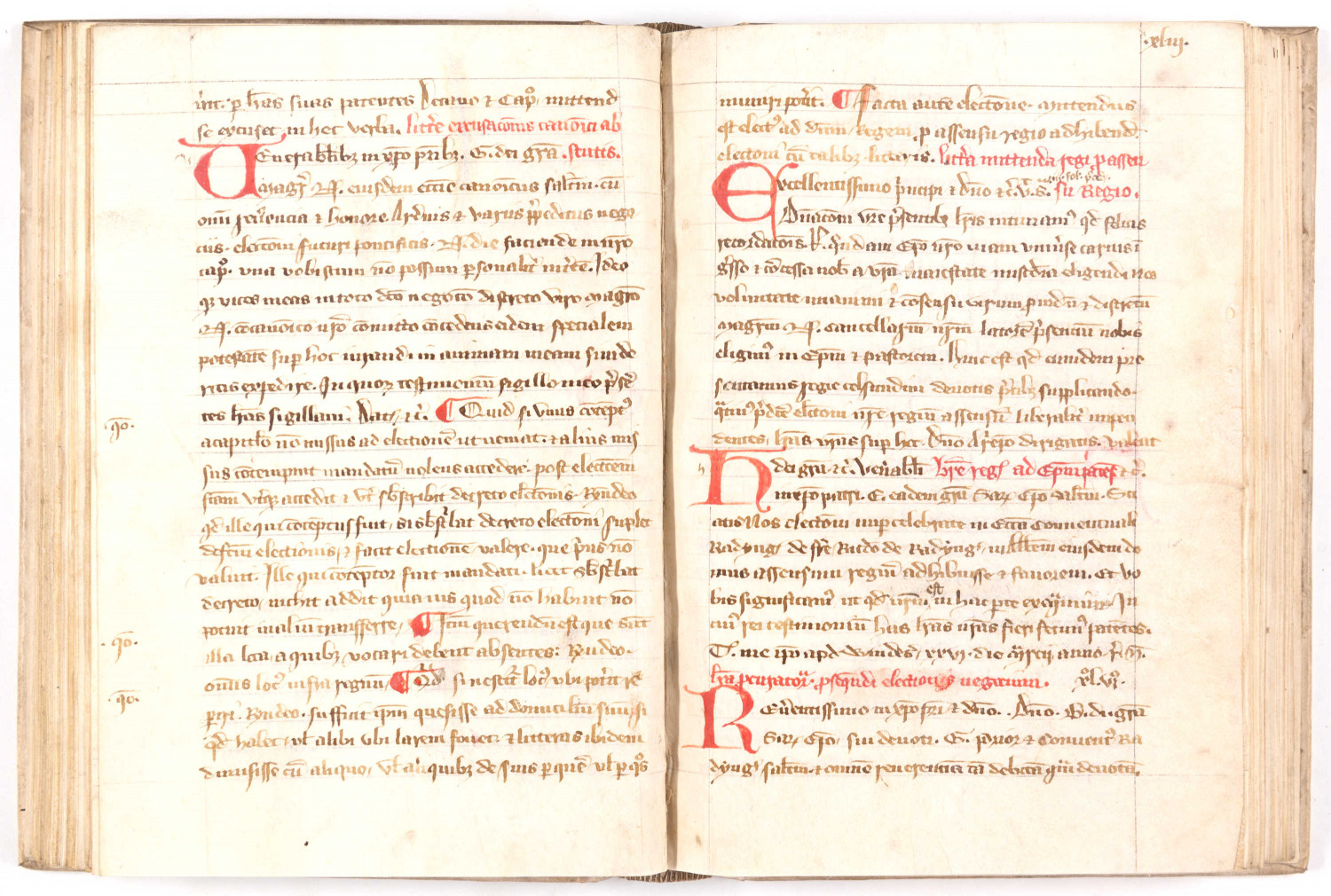

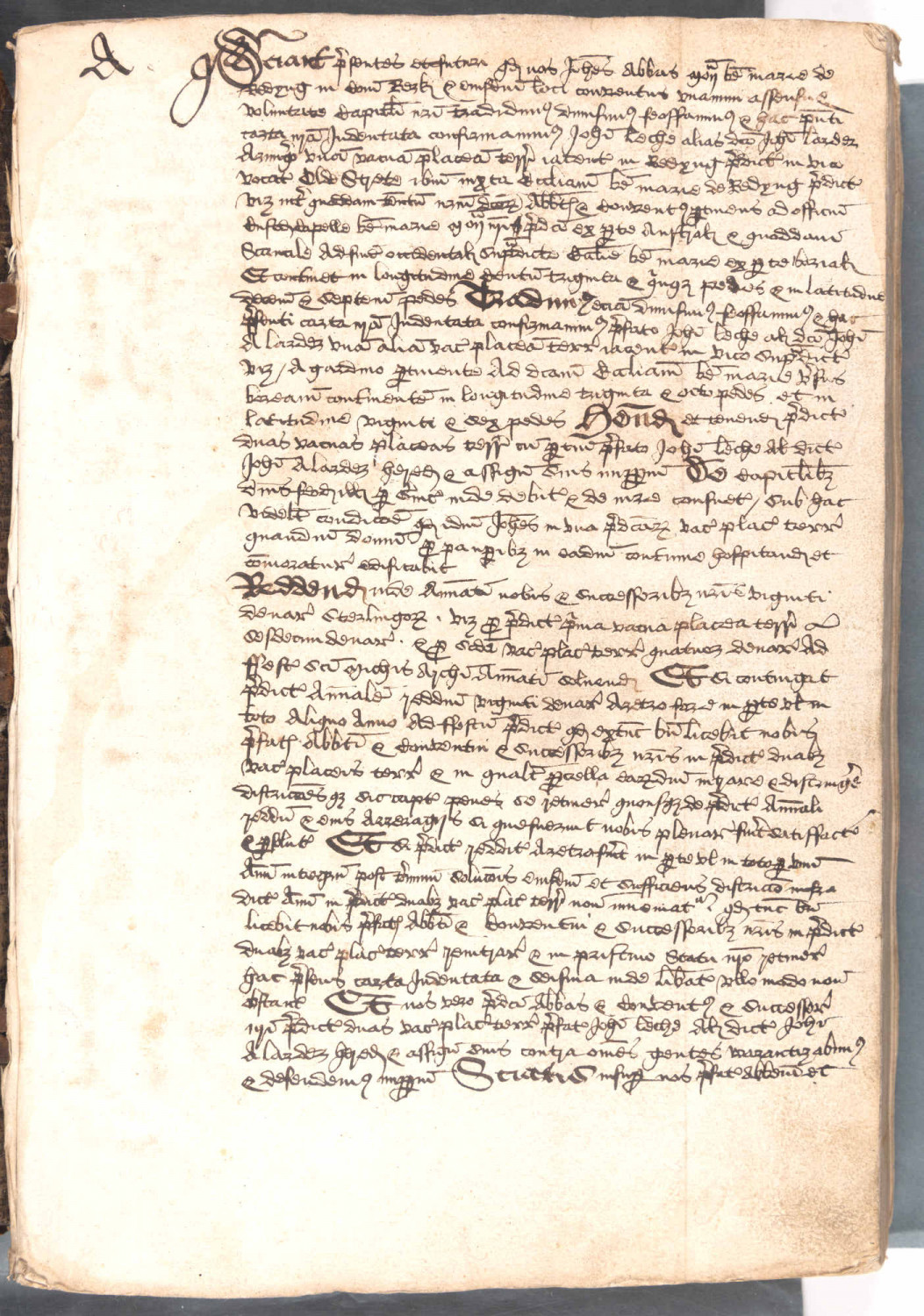

D/EZ176/1 - Reading Abbey formulary

The Reading Abbey formulary, n.d. [c.1340s] is one of the few surviving documents from the abbey’s own archive. It was held in private hands until RBA purchased it in 2012, thanks to a grant from the Friends of the National Libraries.

Mostly in Latin with a few sections in Old French, the text was written in a single hand in iron gall ink with red section headings on vellum folios (5 ½ x 8 in). The pages were evidently trimmed when the volume was rebound in the 18th century. It was written as a tract on conveyancing, setting out formulas for types of legal documents, apparently using real examples from the period 1227-1337, mostly from the abbey archives or those of its daughter monastery at Leominster, Herefordshire, and the archives of the bishop of Hereford. It even includes the text of the controversial homage sworn by John Balliol, king of Scots, to Edward I, in 1292 (in French), showing how the country’s religious institutions were used to disseminate important national information.

Another text shows the importance of the wool trade for the abbey. This is a contract with the merchant J de S, to sell him the abbey’s entire wool crop, for three years, at an agreed price (f19v). Such contracts demonstrate the financial difficulties which Reading and other abbeys encountered in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The pages shown are for documents relating to the election by the monks of a new abbot, specifically of Richard Bannister in 1262. Richard was previously the abbey’s sub-prior.

D/EX2064/1- Replica of Reading Abbey seal

This replica of Reading Abbey seal (1328) was produced by Botly & Lewis of Reading, jewellers, as a souvenir of the Reading Pageant, 1920.

One side shows King Henry I holding a representation of the abbey, between St Peter and St Paul, patron saints of Reading’s daughter house at Leominster, the other features the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus in the centre, with St James, whose hand was the Abbey’s most precious relic, on the right (with pilgrim cap and staff), and St John on the left.

The original seal matrix was used by the abbey to validate its legal documents. RBA does not have any original examples of the seal, but some exist in the British Library, and in the archives of Salisbury and other cathedrals.

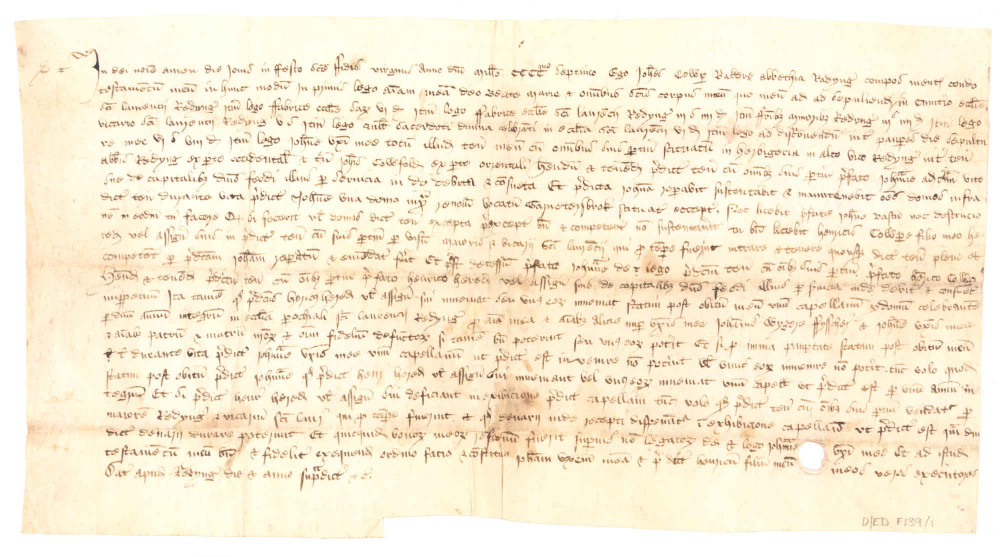

D/ED/F139 - Will of John Cowpar

The will of John Cowpar, baker to the Abbot of Reading, 1407 is written in Latin and is a very early survival for any will.

John Cowpar was not a monk, but a lay employee, who lived in the High Street, Reading, with his second wife Joan. It was standard practice for the abbey to employ secular staff and this shows how intertwined it was with the daily life and community of the town. John was probably paid both in cash and in kind.

The fact that John was wealthy enough to leave a will demonstrates the high status which skilled artisans working for the abbey could achieve. He was probably in charge of all baking for the abbey, and will have been responsible for an important part of its daily food supplies. His duties would include checking the quality and size of all the abbey’s loaves, and ensuring their safe delivery to the cellarer and to officials responsible for various offices within the abbey and its precincts.

R/AT 1/113 - Grant by the burgesses and community of Reading

This is a grant by the burgesses and community of Reading assembled in the Gildhall, to Simon Port[er], mayor of Reading, and his successors, on Friday, after Michaelmas, 8 Henry VI [30 September 1429]. It was for an annual rent of five marks from the common chest of the Gildhall, to be paid by the cofferers (Keepers of the joint chest – the financial officers of the gild), in exchange for Simon's quitclaim on behalf of his successors of rights to all the rents, lands and holdings of the Borough.

This was Simon Porter’s first term of office as mayor; he served again in 1441-2 and 1450-1.

The arrangement illustrated by this deed was rather like the way the Queen has handed control of the Crown Estate to the government in return for payments from the Civil List. If the payment was in arrears, the mayor could distrain, or seize, this property. Simon and his successors were still to meet the expense of providing drink, food and gifts for the seneschal (steward) of the Abbot of Reading, the King's justices, jesters and musicians, and in charity to beggars.

The zigzag cutting at the top shows that it was a ‘chirograph’. Two copies were created on the same piece of parchment but then cut apart and handed to each party. Brought together again at a disagreement, the cuts and writing would then marry up if the two documents were placed together.

D/QR4/2 - Account book and rental

This page is from the account book and rental of the Reading properties late of John A'Larder, 1510-1607.

It is from the back of the book and is a 16th century copy of a 1475 deed from John, abbot of Reading, to John Leche alias John (A') Larder, esquire, of two vacant pieces of land in Old Street [now St Mary's Butts] by St Mary's church, Reading, on condition that he build on one of them a house for the poor; 10 September 15 Edward IV [1475].

John Leche or A'Larder, was an abbey steward. The almshouses he built, close to St Mary’s church, supplemented the abbey’s provision. In 1481 the representatives of the town complained to Edward IV that the abbot had kept St John’s almshouse (near St Laurence’s church) empty for many years whilst taking the income from its lands.

In his will, dated 1477, John also left other properties in Reading for the benefit of the poor. Although his original almshouses no longer exist, his charity remains a constituent part of the Reading Almshouse Charity.

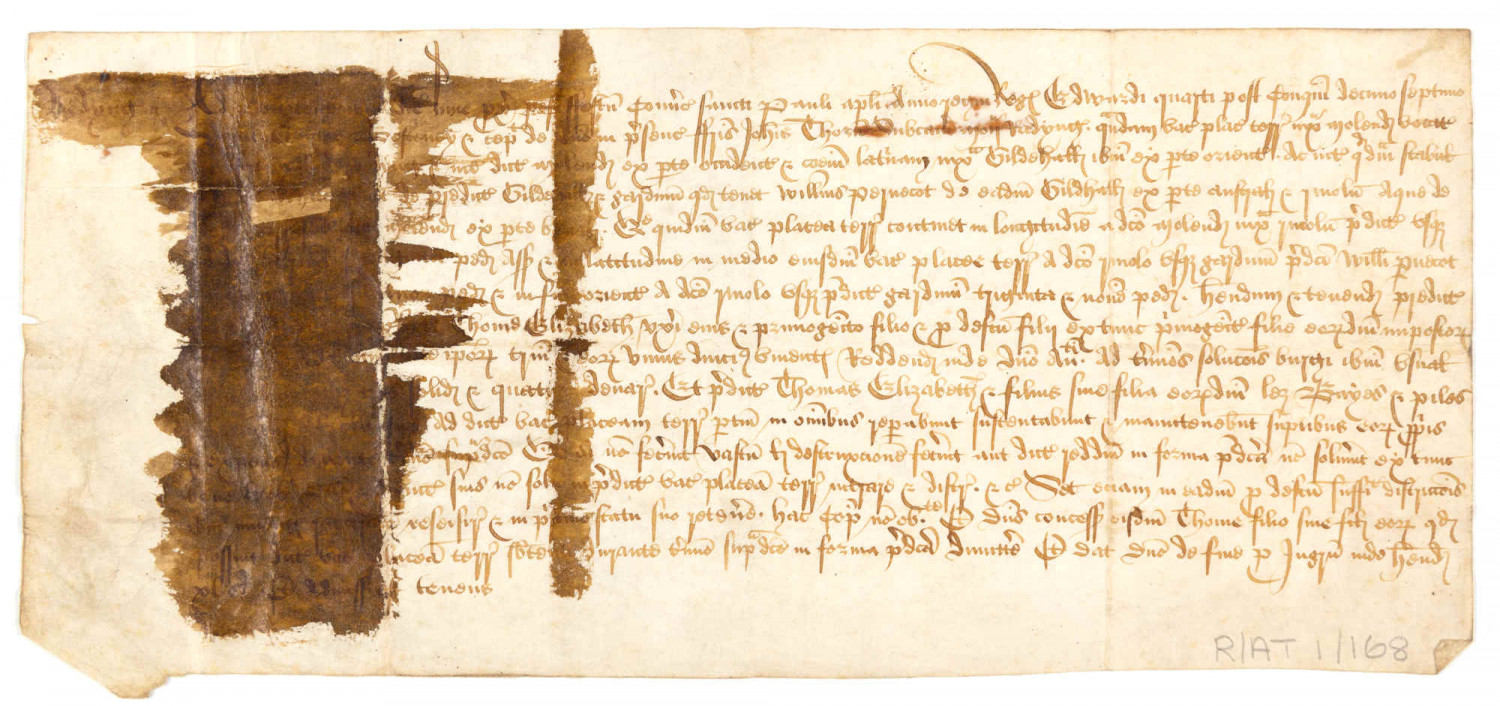

R/AT1/168 - Lease of property belonging to the abbey

This is a lease of property belonging to the abbey dated at Reading, Monday after the feast of the conversion of St Paul the Apostle, 17 Edward IV [26 January 1478].

By this deed Thomas Besteney received from, and in the presence of, Brother John Thorn', subchamberlain of Reading Abbey, a plot of empty land next to [Minster] Mill on the west side and the common latrine next to the Gildhall on the east side, a stable [illegible] belonging to the Gildhall and a garden which William Pernecot holds on the south side and the mill stream on the north side, measuring 60 feet long from the mill to the latrine and 41 feet wide from the mill to William's garden in the middle and 39 feet at the east end. The lease was not for a fixed term, but as was common for the period, for the lives of Thomas, his wife Elizabeth, and their eldest surviving son or daughter, for an annual rent of [?]3s 4d. Thomas, Elizabeth and their son or daughter were to [stake out] the plot and keep it in [repair], on pain of distraint (seizure). Thomas paid 40 marks entry fine.

This deed was almost certainly part of the abbey archives and later inherited by the corporation. Keeping the boundary fences in good repair would be important, not least since many families kept pigs and so many of them roamed the streets of the town that an officer was appointed to deal with them in 1474. The use of the land is not specified in the deed.

The staining is the result of varnishing in the late 19th or early 20th century.

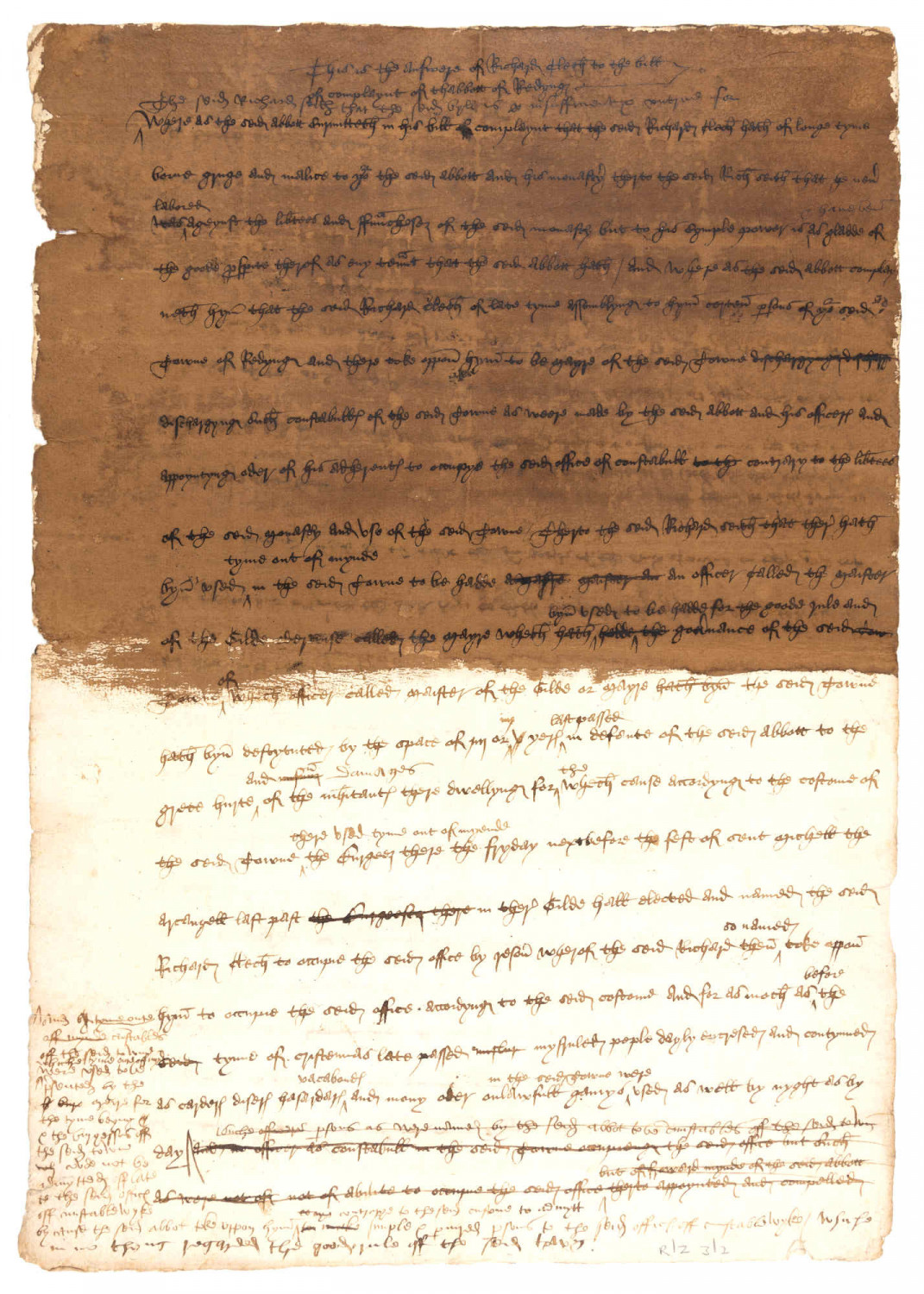

R/Z3/2 - Draft answer of Richard Clech[e]

Draft answer of Richard Clech[e] to a bill of complaint brought against him and others by the abbot of Reading, n.d. [c.1498].

Richard Cleche was mayor of Reading, 1487-1489, and master of the gild and de facto mayor, 1498-1499, in one of the worst periods of conflict between abbey and borough. This began in 1487 when the new king, Henry VII, granted what became known as ‘the king’s great charter of the liberties of the Gild Merchant of the borough of Reading’. This gave the mayor effective control of the cloth trade in the town. Even more significantly, the mayor and burgesses were given perpetual rights which increased their legal status.

In this document, in English, Cleche defended his election as mayor by the burgesses on the grounds that the abbot had failed to appoint a mayor or master of the gild (as he was supposed to do according to the 1254 agreement) for three or four years in a row. Cleche defended his appointment of Thomas Carpenter and William Netter as constables because the previous Christmas had seen 'mysruled peple dayly encresed and contynued as carders, disers, hasardars, vacabonds and mony oder onlawfull gamys' in Reading, both day and night, and the abbot's chosen constables were 'simple & perjured persons' who 'in no thyng regarded the good rule off the seid town'.

Cleche also defended himself and his followers from the charge of breaking the town stocks and making new keys for use by his constables. He argued that the stocks had been made and kept in repair at the expense of the burgesses, but that the keeper of the keys (appointed by the abbot) had refused to hand the keys over, resulting in new locks, bolts and keys needing to be made.

This dispute continued for years until it was finally settled in 1507 in a case heard by the Lord Privy Seal and the King’s Chamberlain. A compromise was reached which sustained the rights of the abbot while acknowledging the newly-corporate mayor and burgesses.

The document, on paper, is badly stained by varnishing, and parts are difficult to decipher.

R/AL1 - Award by Thomas Englef[i]eld

Award by Thomas Englef[i]eld, serjeant at law, and Walter Luke, gentleman, arbitrators between the abbot and convent of Reading Abbey and the mayor and burgesses of Reading, concerning a dispute over the title to: certain butchers’ shops and 'standyngs' (market stalls) called the Flesh Shambles or Out-butchery; and an empty piece of ground between the common 'seage' of the gildhall and Minster Mill; and an empty piece of ground between the Fish Shambles [and] the east end of the Flesh Shambles, dated 18 November 17 Henry VIII [1525].

Thomas Englefield appears as a signatory to an order setting out the procedure to be followed in appointing burgesses of Reading, approved by the King’s Council at Windsor in 1510. This would suggest that he was familiar with the town and its affairs.

The abbot in 1525 was the ill-fated Hugh Cook (Faringdon), the last abbot, who was appointed in 1520. He and the mayor agreed on two trusted arbitrators to settle another long-running dispute.

The arbitrators decreed that the mayor and burgesses should peaceably occupy the premises without interruption or denial by the abbot and convent; and that they should rebuild the buildings at the Flesh Shambles, where meat was sold; paying an annual rent to the abbot and convent of 5s, payable in two portions at Lady Day (25 March) and Michaelmas (29 September), for the Flesh Shambles, and 12d for the ground between the gildhall and Minster Mill. The abbot and convent had the right to seize the premises if the rent was not paid within a month of becoming due.

This document is in English, which is unusual for the period. From left to right you can see three seals validating the document: the seal and signature of Thomas Englefield; a seal with impression missing; and the seal of the borough with the five heads visible. This is the borough’s copy of the agreement; the wavy edge at the top is a sign that it was another ‘chirograph’, with the other copy kept by the abbey.

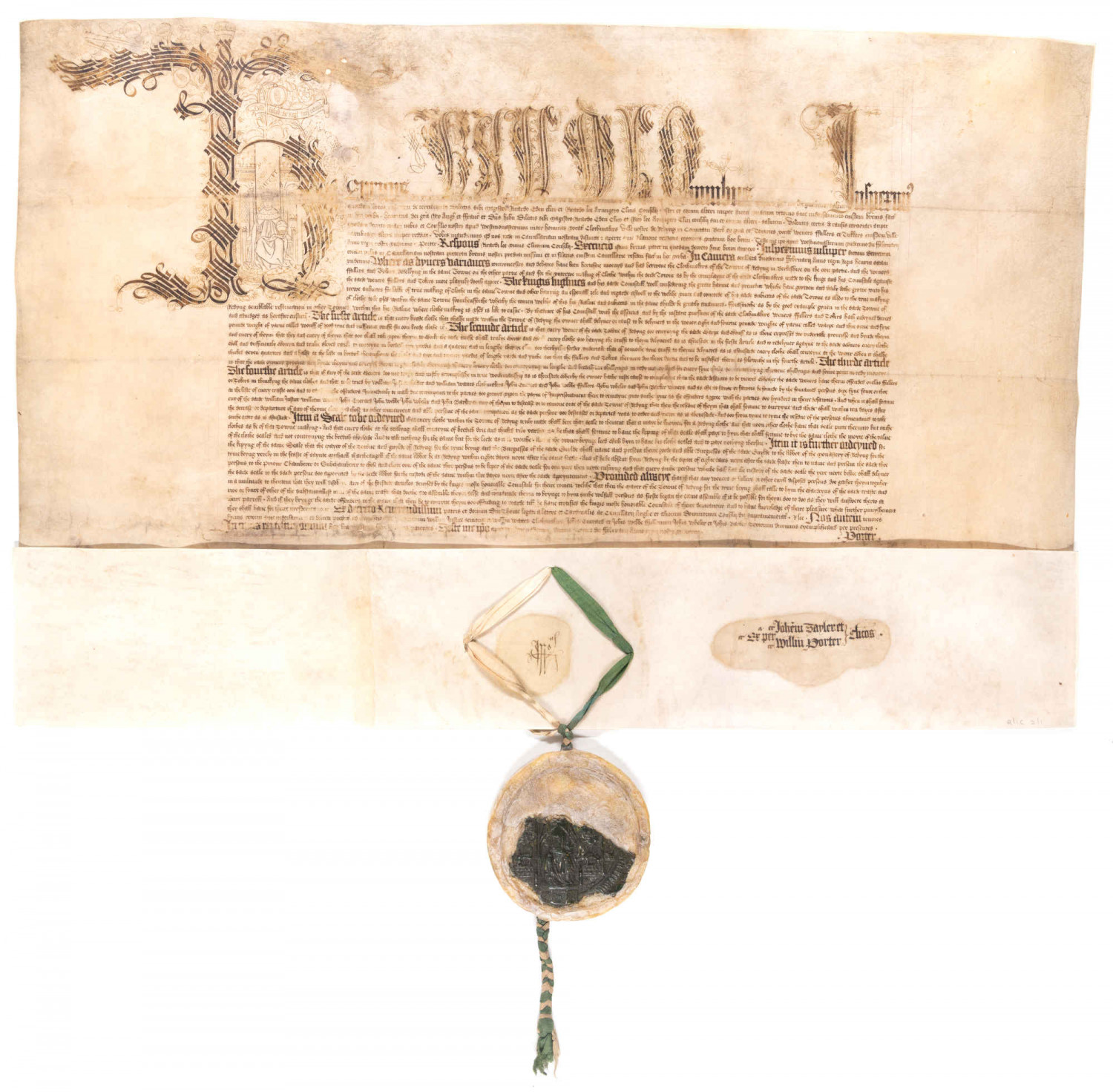

R/IC2/1 - Inspeximus

Inspeximus by Henry VIII of articles for the regulation of clothmaking in Reading, agreed by the clothmakers of Reading on one hand and the weavers, fullers and tokers on the other, in the court of Star Chamber, 1520.

This document demonstrates the rising importance of textile production in Reading. Much of the cloth may have been for local use, since dyers, drapers and tailors appear in the Reading records from the fourteenth century on; but some Reading traders were also selling their goods in London. In the early fifteenth century Reading was already a centre of trade for wool yarn, with flax and linen following by the middle of the century. The value of these trades helps to explain the king’s interest in the town. Reading ranked 21st in the ranks of English tax-paying towns and cities in 1524-25.

In the top left hand corner is a portrait of Henry VIII (known as a portrait initial because it is placed inside the H of his name). At this point in his reign Henry’s image remained relatively close to those of his father, Henry VII. The famous image created by Holbein was not issued until the 1530s.

The articles are in English, for the benefit of the tradesmen, with legal confirmation in Latin. They set out the approved weights of warp and woof yarn required for a broadcloth, the size of the finished broadcloth, prices for weaving linsey and fine cloths, penalties for poor workmanship, and the marking of all cloths made in Reading with a seal, to be kept by a person appointed annually by the abbot of Reading Abbey.

The document also includes a provision "that if any wevers or fullers or other evyll disposid persons doo gather theym togither in a multitude to th'entent that they will disobeye any of the forsaide articles" the mayor was to call on the wardens of the craft and order them to produce the ringleaders to be committed to prison.

The seal is damaged and has been repaired; the darker coloured parts are what remains of the original.

Click through to Part Two: After the Abbey or go back to the Reading Abbey page.

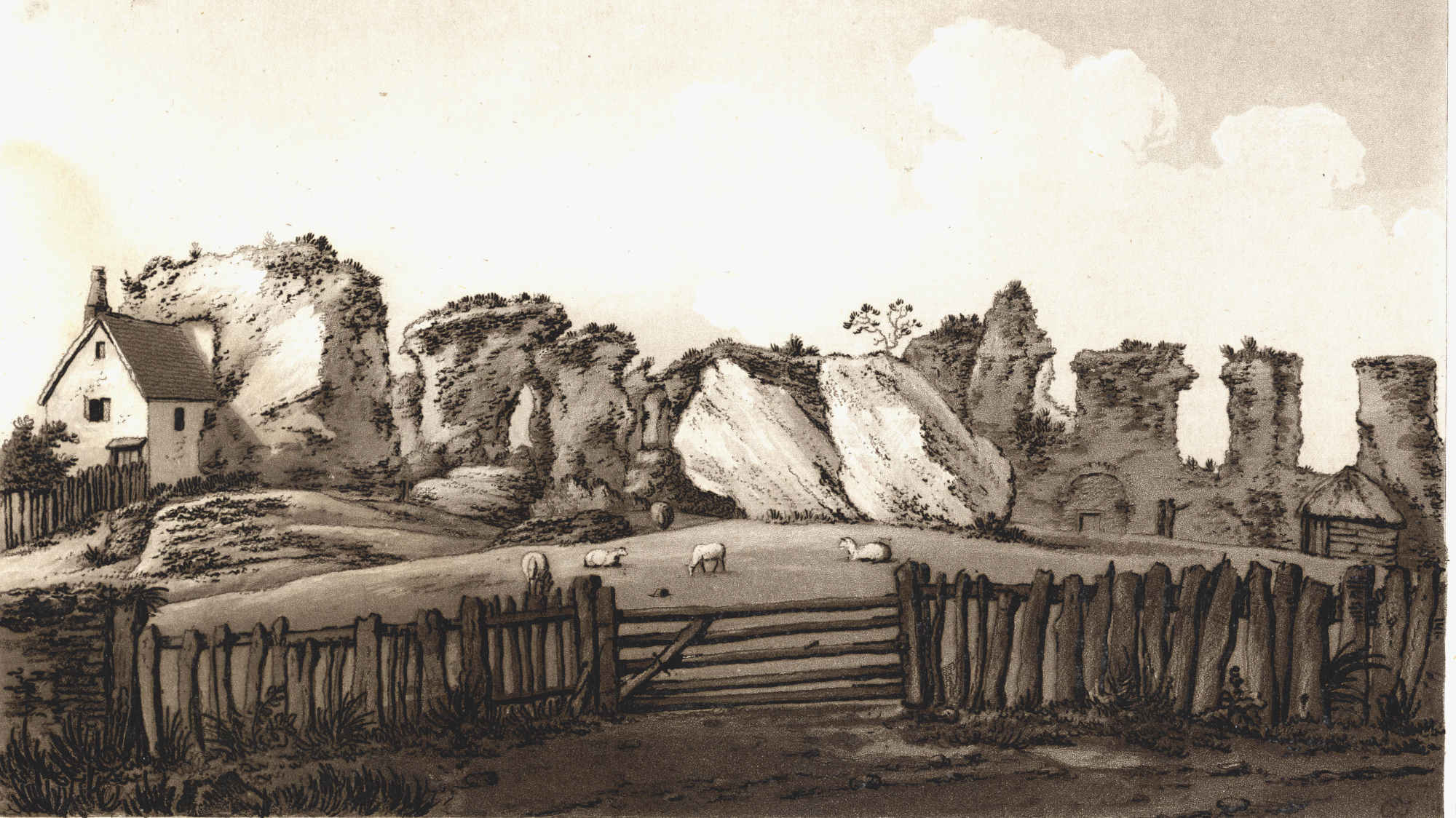

For current information about the Reading Abbey ruins, visit the Reading Abbey Quarter website.