The Berkshire Record Office: how it all began

(Part one of an article written in 2008; note that the name changed from the Berkshire Record Office to theRoyal Berkshire Archives on 10/08/2023)

This year (2008) sees the 60th anniversary of the creation of the Berkshire Record Office. Today, BRO includes seven linear miles of shelving in a suite of purpose-built and environmentally controlled strongrooms, together with research space for up to 50 people, a multi-purpose function room for talks or exhibitions, and a bespoke conservation studio. But it wasn’t always like that, and the development of the RBA can be seen alongside the growth of family and local history research over the same period.

Our story begins nearly 70 years ago, just before the outbreak of World War Two.

Hitler intervenes, though not personally

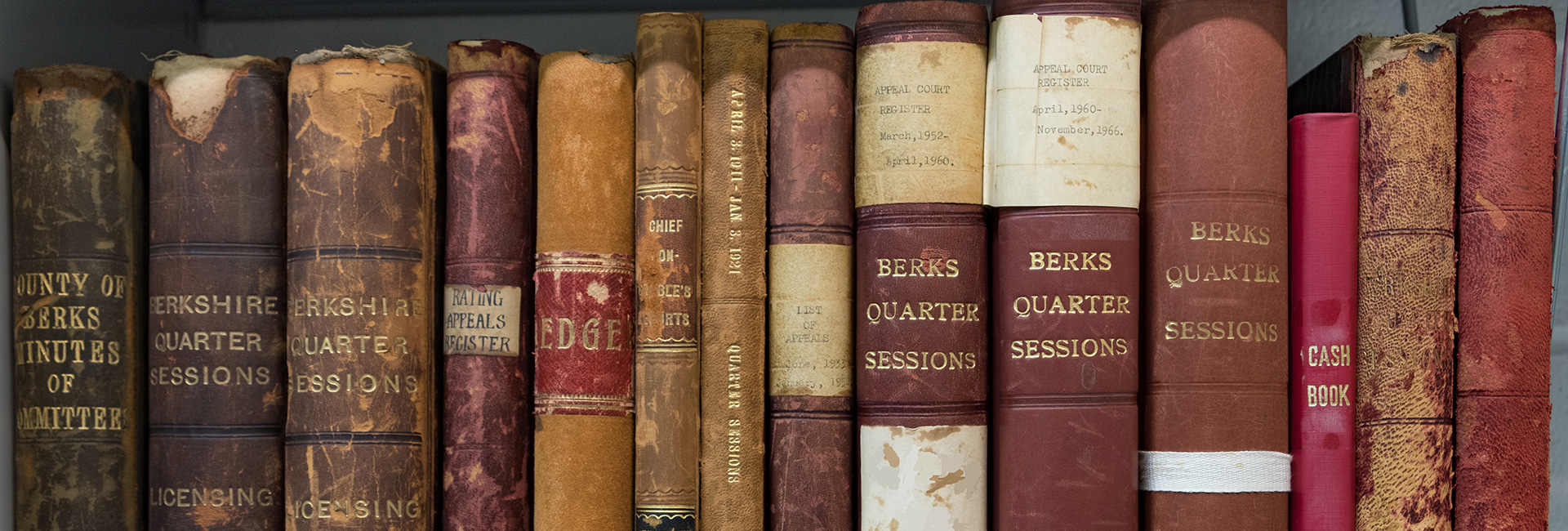

By 1939, 20 English shire counties had established a County Record Office. Berkshire was not one of them. A few years previously the Clerk to Berkshire County Council, Mr Harold Neobard, had gained approval from the Master of the Rolls to store manorial records. Within three years around 500 documents had been deposited with the Council, in addition to the Quarter Sessions and other county records already they held.

A County Records Committee was constituted in the February, and met for the first time on 11 July 1939 at 2.30pm. It received a ‘confidential’ report from the Clerk, who reported that ‘I have been forced to the conclusion that the time has arrived when the Council should engage an archivist and set up a Muniment Room’. The Committee agreed to appoint an Archivist from 1 April 1940 on the salary of £250.

War, however, intervened, and no appointment was made. Documents continued to be collected though, notably in 1943 when the Poor Law Guardians’ records were transferred. The Committee next met on New Year’s Eve 1947, and agreed again to appoint an Archivist, although this time on a salary of £450. Felix Hull was duly recruited from Essex Record Office, and began work on 10 August 1948. It is this date that we are celebrating as the true start of RBA.

First things first

Felix’s first task was to take an inventory of his inherited collections. His office accommodation and a research area (‘Student’s Room’) were provided in the basement of the old Shire Hall in The Forbury, Reading. The first visitors would have found some similarities with today – no bags, no smoking, please sign the visitors book – but were required to give at least 3 days’ notice of wanting to visit, had to supply a reference from a JP or public body and could bring in pens if they wanted. The Office was open Monday to Friday, from 9.30am-1.00pm and then 2.15pm-5.00pm, and anyone engaged in business research (including family history work on behalf of others) had to pay 6s 8d per hour. Tracing a map would set you back a further shilling.

The first customers were a mix of academics and local antiquarians. Felix’s first searcher was Sir Henry Braund of Upton, who came in on 13 August 1948 to look at the Upton enclosure award. By the end of the year Felix had received 21 visitors. He held his first group visit to the Office in July 1949, when 35 members of the Reading Institute of Education came round to look at a display of Finchampstead and White Waltham records.

The first strongrooms were also in the basement of Shire Hall, and might better be described as vaults. Doors and windows were a source of worry, but they had been racked with Edwardian iron when built, and the size of those racks has influenced our box sizes to this day. Towards the end of 1951, the Record Office moved next door into the basement of the old Assize Courts (now part of Reading Crown Court). For the first time, the Record Office had a proper searchroom, with space for 12 visitors, and gained a further three vaults. By 1959 it had also gained a repair room, though it had no conservators on the staff.

The Record Office had to operate side-by-side with Court business. One of the vaults was off the corridor which led to the cells, where prisoners were caged on the day they were awaiting trial. When the court was sitting, Record Office staff had to ring a bell to be let through into the vault to retrieve documents. If a prisoner was considered dangerous, the warders would refuse access, and searchers would have to be asked to come back to view their document another day. The searchroom door was also at the foot of the stairs leading to the cells, and it was not unknown for loved-ones to rush into the searchroom, intending to give a fond farewell to a prisoner before he was sent down.

It was a very different time, with different attitudes. When County Archivist Will Smith sought to increase the number of staff from four to five in 1964, he said ‘that since some of the work connected with the reception, storing, and production of records is heavy for females, there is urgent need for an additional male officer of junior rank’ and that ‘a junior appointee was envisaged’. He could later report that ‘no junior applicant (the youngest being aged 22, who was found to be unsuitable), the post has therefore been filled by a middle-aged man’.

She’s leaving home

By the time the first Royal Berkshire Archive shut its doors on 1 October 1980, it barely resembled the little office set up by Felix Hull over 30 years before. During its final year in the old Assize Courts it had received 2,553 visitors. Family and other leisure historians were beginning to swell the ranks, and letters of introduction had long since been abandoned. The opening hours were now 9.00am-5.30pm Monday-Wednesday, 9.00am-7.30pm on Thursday, and 9.00am-4.30pm on Friday (though a lunchtime closure remained from 1.00pm-2.15pm each day). RBA had gained more office space and a further vault too, and also taken on the Reading Borough archives at Tilehurst Library, and a further store in Minster Street. Altogether it controlled 2 miles of shelving. It had also seen its staffing increase from one to ten, with the first conservator having finally been appointed in 1972.

By the time that County Archivist Angela Green wrote her annual report in 1978, she concluded that it ‘has again been a year not without its problems, one of the greatest being the cramped accommodation in the offices, the searchroom and the strongrooms. The hope of improved quarters in the new building, however, draws nearer’.

That new building was the new Berkshire County Council headquarters, the Shire Hall at Shinfield Park. A new county headquarters had been planned since the 1960s, and the Shinfield Park site was chosen only after plans for new offices close to The Forbury were abandoned. The Record Office’s part in the move began on 5 December and carried on until 15 January. Almost inevitably, the accommodation wasn’t ready, and work continued to complete it beyond the re-opening of the new Office on 26 January 1981.

So Office one was no more, and Office two would be the RBA’s home for the next 20 years. The challenges of the first RBA had been to deal with rapid expansion – of collections, of storage, and of enquiries. These challenges would be magnified in the information explosion that was to come.

Read part two of this article covering 1981 to 2008.

Since this article was written, the RBA became an Accredited Archive Service in 2017. Accreditation defines good practice and agreed standards for archive services across the UK and is led by the National Archives (TNA). Following a review in 2020, the panel 'commended the service's sustained effective work'. You can find out more about the Accreditation process on the National Archives website.